Help Unlock Your Students Potential & Revolutionise Your Teaching Approach with The Young People Index®.

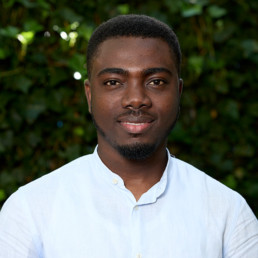

Written by Cecilia Harvey

A quadrilingual Social Anthropologist whose passion for the richness of diversity and the psychology of the human race, Cecilia focuses her Equity, Diversity & Inclusion work on connecting people through difference. As a subject matter expert, Cecilia has driven and coordinated strategic initiatives centred around identity, gender, LGBTQ+, ethnicity and disability, working with multiple stakeholders. Accomplished in designing training programmes such as unconscious bias awareness, microaggressions and inclusive language, Cecilia’s deep understanding of culture, psychology and behaviours has allowed her to become an Accredited Facilitator in Cultural Intelligence (CQ ®).

When we work with young people in an academic setting it can sometimes be difficult to grasp some of their unique attributes as they all learn the same curriculum. During these years, these young people have likely not yet developed the self-awareness to understand how they can best harness their skills. What benefit would a better understanding of your student’s natural proclivities in terms of the way they work have in your classroom?

The Young People Index® (YPI) is a digital online assessment tool designed for 13-18 year olds to help individuals identify their natural energy when it comes to working in groups / teams, now and in the future. This is vital in deepening a young person’s self-awareness and builds confidence in how they work with others, and in teams.

The Young People Index® can considerably improve the performance and engagement of young people and help teachers, youth workers, and sports coaches to understand the unique contribution each young person makes, or has the potential to make (their energy for impact!). This knowledge can be used in many ways, some of which are: to develop questioning skills, adapt teaching and communication methods, and analyse group dynamics to create more impactful results, be this in the classroom or on the sports field.

The Young People Index® is a product from the The GC Index®, a similar tool that focuses on adults and their impact in the workplace (over 18s). The YPI helps young people at a much earlier age, enabling them to consider environments where they will thrive, not just survive!

What are the benefits to students?

The YPI measures a young person’s energy to make an impact in a team, project, or future organisation and does not measure academic ability. This knowledge of their energy to make an impact can benefit them in various ways:

- Boosting self-awareness, leading to increased confidence in their ability to make an impact on the world. The YPI encourages young people to consider career opportunities aligned with their interests and unique energy for impact.

- Discovering their unique contribution to a team, supporting teamwork and communication.

- Enhancing interview skills by helping them to articulate their unique impact and how they are best utilised in a team at an interview.

- Exploring their leadership potential.

- Identifying areas where they have less energy for impact to build awareness of the need for complementary team members—perfect for aspiring entrepreneurs!

- Facilitating better relationships with teachers and creating optimal learning conditions.

How does it work in practice within Schools?

When a young person completes the online questionnaire, a personalised report is generated, guiding them toward areas where they can thrive based on their unique proclivities.

In Schools, the YPI is usually used as part of an existing career guidance framework. Students complete the assessment at school and then either an in-house trained teacher, or external YPI trained consultant works with the students over the course of term, running workshops that focus on building self-awareness, team working, leadership, and an understanding of personal and organisational values, and how to choose an organisation in the future that aligns with these.

The YPI’s insights significantly improve performance and engagement, whether in the classroom or on the sports field. It’s a powerful tool for shaping young individuals’ futures!

Find out more about us by visiting our website www.youngpeopleindex.com

To download case studies & our brochures, click here.

To arrange a discovery call, email Cecilia Harvey, Accredited YP Gcologist cecilia@culturalnexus.co.uk.

Supporting our neurodivergent girls with their Relationships and Sex Education

Written by Alice Hoyle

Alice Hoyle is a Wellbeing Education Consultant specialising in Relationships Sex and Health (RSHE) Education and Sensory Wellbeing with a special interest in Neurodiversity and girls. She has worked as a teacher, PSHE lead, Youth Worker, LEA Education adviser and now works with local authorities, academy chains, universities and schools. She has authored 3 very different books on mental health, RSHE and sensory wellbeing.

As an education consultant of over 20 years experience in Relationships Sex and Health Education (RSHE), and a neurodivergent (ND) mum of ND daughters, I am passionate about supporting this group of girls with their RSHE. So here are some of my top tips for doing this work:

- Support them to practise tuning into their guts & listening to their ‘spidey senses’

Teach girls to tune into their own bodies as much as possible, recognising that any issues with interoception/ alexithymia may mean this will need constant revisiting. The emotion sensations feelings wheel may help here. Use the model of ‘comfort, stretch, panic’ from our book Great Relationships and Sex Education to support understanding when to speak out and get help and who their trusted adults are.

- Embed the Ethical Relationships Framework across everything

Use this ethical relationships framework to help the girls understand what they should expect from their relationships from Moira Carmody and Jenny Walsh (page 11 and also in Great RSE).

- Taking Care of Me (meeting your own needs)

- Taking Care of You (balanced with meeting the needs of the other person)

- Having an Equal Say (making sure there is no coercion, control or power imbalances)

- Learning as we go (nobody is born perfect at relationships, there will be periods of rupture and repair or sometimes ending)

Constantly revisit and reinforce these simple ‘rules’ for ethical friendships and relationships so they become embedded across their interactions.

- Explore ND specific nuances to ethical relationships

To build on this ethical relationships work, discuss masking and how we should feel safe enough and able to unmask with people we care about and trust and what that could look like (Taking care of me and you). Explore verbal and non-verbal ways of communicating our needs as well as how we can learn to tune into other peoples verbal and non-verbal cues. Explore the double empathy problem as a challenge for Neurotypical (NT) and Neurodivergent (ND) interactions. (Having an equal say and learning as we go).

- Unpick social norms and expectations particularly around gender.

Challenge gender stereotypes and celebrate what it means to be a neurodivergent female. The Autism Friendly Guide to Periods, Different not Less and The Spectrum Girls Survival Guide are fab resources to have in the room for students to flick through if in need of a diversion if the main subject of the lesson becomes overwhelming! Use resources such as this Padlet , the Autistic Girls Network and Girls have autism too.

- Deconstruct Idioms and use clear language

There are many idioms around relationships and sex that can be confusing for ND young people; ‘Voice breaking’; ‘bun in the oven’; ‘Netflix and chill’; ‘don’t give sleeping people tea’. You will need to do some research into the current ones for your cohort and help your group deconstruct them so they can ascertain the real meaning. Use correct words and not euphemisms for body parts. It is especially important to explain what a vulva is (a terrifying number of folk think it’s a type of car!).

- Use Games and Objects to increase engagement and practise communication skills.

Use low pressure talking games like Feel good jenga (sentence starters on jenga blocks which works phenomenally well with ND pupils) or Attractive and Repulsive qualities in a magnet game to for discussions in low stakes fun ways. Build in opportunities for Object Based Learning, by getting models you can handle means the girls can really understand things in a more tangible way.

- Teach consent in direct ways.

Avoid using the “tea and consent video” as it is an unhelpful confusing analogy. There are lots of different ways you can educate about consent. Parents and Teachers often don’t like hearing ‘No’ and societal expectations teach us that girls are supposed to be agreeable and passive. Therefore, it can be really helpful to go back to basics with teaching the 3 part No and the 3 part responding to a No.

- Saying No: Firm body language, unsmiling facial expression, and a loud, clear “No.”

- Hearing No: Stop immediately, check in with the person, and suggest an alternative activity.

You can have a lot of fun practising saying and hearing NO and exploring role plays and social stories to build confidence with asserting boundaries! There is of course an important caveat that if a No is ever overridden and an assault happens it is not the victim’s fault, blame lies with the perpetrator, and there is always a trusted adult (help the girls identify who they are) who can help.

- Understanding the senses can support understanding of sensuality and pleasure.

Research shows that good sex tends to be safer sex. Where appropriate (depending on the age and stage of development of the young woman) you may want to include safe conversations about forms of intimate self touch, (this could be stimming, sensory seeking or masturbation) as well as conversations about sensuality. More generally we need to do much more work on supporting ND girls to understand and advocate for their own sensory needs. Developing their sensory autonomy will go a long way in supporting their understanding of consent and bodily autonomy in relationships.

For more help doing this work then please get in touch via my website www.alicehoyle.com. Good luck!

Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Doors: A Metaphor for the Diverse Curriculum

Written by Hannah Wilson

Founder of Diverse Educators

In the dynamic landscape of education, the curriculum serves as the foundation for shaping young minds. As we strive for a more inclusive and representative educational experience, the metaphor of Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Doors offers a powerful framework for curriculum development. This metaphor, introduced by Dr Rudine Sims Bishop, encapsulates the essence of diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging within educational content, emphasising the importance of reflection, observation, and engagement for all learners.

Mirrors: Reflecting Students’ Own Lives

Mirrors in the curriculum are essential for students to see themselves – their cultures, identities, and experiences – reflected in what they learn. When students encounter stories, histories, and perspectives that resonate with their own lives, they feel validated and recognised. This reflection fosters a sense of belonging and self-worth, which is crucial for their overall development and academic success.

For curriculum specialists and subject leaders, this means incorporating diverse voices and narratives across all subjects. For example, in literature, selecting texts from a variety of authors who represent different backgrounds ensures that every student can see themselves on the page. In history, presenting a more inclusive perspective that acknowledges the contributions and experiences of marginalised groups and provides a fuller understanding of the past.

Windows: Viewing Others’ Lives

Windows offer students a view into the lives and experiences of people different from themselves. Through these glimpses, learners develop empathy, understanding, and a broader perspective of the world. Windows help dismantle stereotypes and prejudices, fostering a more inclusive mindset among students.

To create these windows, educators need to curate a curriculum that includes global perspectives and diverse narratives. In geography, this might involve studying various cultures and their relationships with the environment. In science, discussing contributions from global scientists highlights the universal nature of discovery. Providing opportunities for students to engage with content that portrays different lifestyles, beliefs, and challenges cultivates an appreciation for diversity and interconnectedness.

Sliding Doors: Engaging and Interacting

Sliding doors represent opportunities for students to enter into, and interact with, different worlds. This element encourages active engagement and personal reflection. When students can metaphorically ‘step into’ the experiences of others, they gain deeper insights of different identities and build meaningful connections.

Interactive projects, collaborative learning experiences, and role-playing activities serve as sliding doors in the curriculum. For instance, a history project where students re-enact historical events from multiple perspectives can provide profound learning experiences. In literature, writing assignments that ask students to create narratives from the viewpoint of characters unlike themselves can deepen empathy and understanding.

Integrating Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Doors

To integrate these concepts effectively, curriculum specialists and subject leaders must be intentional and thoughtful in their approach. This involves:

- Reviewing and Revising Existing Curriculum: Conducting thorough audits to identify gaps and biases. Ensuring that the content reflects a diverse range of voices and perspectives.

- Collaborating with Diverse Communities: Engaging with parents/ carers, community leaders, and organisations to gather input and resources. This collaboration can enrich the curriculum with authentic, representative materials.

- Providing Professional Development: Equipping teachers with the skills and knowledge to deliver an inclusive curriculum. Training on cultural competence, unconscious bias, and inclusive teaching strategiesl.

- Utilising Technology and Media: Leveraging digital resources to access a wider array of content. Using online platforms, virtual exchanges, and multimedia can bring diverse voices and experiences into the classroom.

- Encouraging Student Voice and Choice: Empowering students to share their stories and choose projects that reflect their interests and identities. Designing student-centred approach fosters a sense of ownership and relevance in their learning.

The metaphor of Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Doors provides a robust framework for creating an inclusive and representative curriculum. By reflecting students’ identities, offering insights into others’ lives, and facilitating active engagement, educators can cultivate a learning environment that values diversity, promotes equity, centres inclusion and builds belonging. As curriculum specialists and subject leaders, embracing this metaphor not only enriches the educational experience but also prepares students to thrive in a diverse and interconnected world.

Should schools provide prayer spaces?

Written by Zahara Chowdhury

Zahara is founder and editor of the blog and podcast, School Should Be, a platform that explores a range of topics helping students, teachers and parents on how to ‘adult well’, together. She is a DEI lead across 2 secondary schools and advises schools on how to create positive and progressive cultures for staff and students. Zahara is a previous Head of English, Associate Senior Leader and Education and Wellbeing Consultant.

The recent High Court decision, ruling in favour of headteacher Birbalsingh’s decision to ban prayer spaces has created quite the media storm. The decision has raised concerns about the precedent it sets for schools creating safe spaces for students and staff, Muslim students and staff in particular. It has also raised conversations about what schools are for and how schools and workplaces can fulfill their obligation to adhere to the Equality Act and The Public Sector Equality Duty – and how they can get around it too.

The responses to the verdict reveal that we live in a society and online world in which Islamophobia and anti-Muslim hate is increasing; whilst we have ‘come a long way’ in overcoming Islamophobia since 9/11, a high court ruling like this makes me wonder if we’ve made any difference at all to the safety of Muslims for future generations? The verdict also reveals the disconnect that exists within the school system itself: we have some leaders who are not interested in creating unity and understanding within a diverse country – yet at the same time they ‘tokenistically’ take pride in multiculturalism too. And, we have other leaders in education giving us hope, embedding inclusive and equitable practices in everyday school life. I find it baffling that a simple question about prayer spaces ends up at the gates of a High Court. To me, this not only reveals a lack of unity and understanding in a school but also an absence of a critical skill that should be at the centre of schooling: listening.

Many educators and commentators have been sharing their concerns and outrage about the decision. It will also concern parents and students who regularly use prayer spaces in schools, maybe even at work (many teachers use prayer spaces too). It’s a disappointing decision and whilst several anti-woke keyboard warriors rejoice at the ruling, we cannot let it set a precedent for schools – and I don’t think it will. Schools absolutely should provide prayer spaces and they will continue to provide such safe spaces for students – it’s quite simply common sense. For this blog, examples and explanations are practical and experiential, based on what life is like ‘in school’. Whilst research and data are important, progress, collaboration and community cohesion are also nurtured by listening to the candid, lived experiences of staff and students in schools.

Time and space to pray

In line with the Equality Act, allowing students and staff to pray is reasonable and proportionate to a school and working day. It is comparable to allowing students to have break times, music lessons and god-forbid, toilet breaks. Different forms of prayer and spiritual practice are a part of nearly every faith. In Islam, praying 5 times a day is an integral part of the faith. It takes 5-10 minutes to pray. For the duration of that time, a prayer mat takes up just as much space as a two-seater desk. Depending on the time of year, prayer usually fits into a lunchtime. Just as schools host extracurricular clubs, music lessons sports fixtures and more, prayer can usually fit into this time too. It is not a big ask and it is not disruptive.

Some schools may have a designated prayer room, which is great. Other schools may allocate a classroom, usually near a space where a teacher is ‘on duty’ anyway; the last time I checked, prayer doesn’t require back flips, cartwheels or balancing on one’s head…the health and safety risks are fairly manageable. Some schools might even say, ‘if you need to pray and you have what you need with you (prayer mat, head covering, beads, holy book etc…), feel free to use a designated safe space. It does not need to be complicated.

Prayer spaces are not the problem

To blame prayer and collective worship for peer pressure and bullying is deflecting from the real problem. If children start praying as a result of seeing others pray, or if they simply observe with questions and curiosity, why is this such a problem? If they find it to be a positive experience, surely that can only be a positive learning experience. If the opposite happens, it’s not necessarily a problem either. Rather, it’s a teachable moment and reveals hostile attitudes any school should be aware of. Knowledge about the prejudices within our communities is the first step to safeguarding young people in education. ‘Cancelling’ or banning prayer spaces is not.

‘Banning’ or ‘cancelling’ (on and offline) doesn’t work. It is a power-based behaviour management tool fuelling a notion that education is based on ‘controlling the masses’. We all learn through conversation, discussion, listening, knowledge, understanding, boundaries and respect, not necessarily in that order. By no means are any of the latter ‘easy’ to achieve, but from working with teenagers I’ve found they’re open to a heated debate, discussion, learning, understanding and compromise.

School is a place of work and I’m not sure why we expect teenagers to just abide by ‘yes and no’ rules with little to no explanation. Plus, if they find a reasonable solution (like praying in a classroom for 10 minutes at lunchtime), what’s the big deal? Secondary school students are a few years away from further education and the workplace, which we all know thrives on innovation, creativity and autonomy. In this case, a blanket prayer ban in a school (their current place of work) completely contradicts the 21st century workplace they will inhabit. It doesn’t make sense.

‘It’s inconvenient: we don’t have time to police prayer spaces’

Like any theory of change, whether that be introducing a mobile phone policy or changes to a uniform policy, navigating any arising teething issues (by students, parents and the community), takes time and flexibility. None of this is impossible if it is built firmly into the school culture, relevant processes and policies. These policies and processes may be safeguarding, anti-bullying, behaviour management and curriculum. All of the above are part of a teacher’s and a school’s day-to-day functions; navigating prayer spaces is no different to introducing a new club or curriculum change. Plus, we somehow managed bubbles and one-way systems post-lockdown…I think schools are pretty well equipped to create a prayer space for all of a matter of minutes in a day!

Prayer is not ‘an add on’

Faith is observed differently, from person to person. It is a way of life, and an ongoing lived experience; for some it is an integral part of their identity and for others it is their identity. Prayer is a major part of several religious practices. Like some people are vegan and vegetarian, prayer is not just a choice and something to switch on and off – it is an intrinsic part of an individual’s life. Some individuals, as far as they possibly can, plan their days, weeks, holidays and more around prayer. Not only is it a religious obligation, it is also a source of wellbeing and peace. In a time where health and wellbeing are paramount in education, denying prayer spaces seems counterintuitive. Enabling some form of space (like we do options on a menu) for individuals to pray is a minimal request and something schools can do with minimal disruption. However, if cracks in the system are revealed and outrage spills online and at the High Court, there are bigger questions and concerns to address.

Schools don’t need to be ‘impossible’ or difficult spaces – and they shouldn’t be made out to be like this either. One high court ruling does not define the state of schooling in the UK. I have too much respect and experience (or maybe good fortune) of working in schools that enable, or at the very least, welcome conversations around inclusion, safety, flexibility and authenticity. None of the latter disrupts mainstream education and a student’s chances of attaining a grade 9. However, many other things do and those are inequitable opportunities, ‘belonging uncertainty’ (Cohen, 2022) and denying the identities of the young people we teach.

Diversity in the Curriculum: The Vital Role of SMSC Subjects

Written by Laura Gregory-White

Laura is an RE Regional Advisor for Jigsaw Education Group. She has over 15 years experience as an educator and curriculum lead across Primary and Secondary.

In today’s pluralistic society, where diversity is a fundamental part of who we are, conversations around diversity in schools and the curriculum are increasingly important. Subjects like Religious Education (RE) and Personal, Social, Health, and Economic Education (PSHE) are vital tools in our curriculum offering. Investing in these subjects, invests in our children and young people’s successful development of the skills and knowledge that help to navigate the complexities of our diverse world with empathy, understanding, and a commitment to social justice.

In Primary schools, where all the teaching staff will have an impact on curriculum development, it is crucial that we are giving them the necessary time and expertise to enable this. From the teachers developing and delivering the individual lessons, the subject leads with oversight for the entire curriculum journey, to the senior leaders who set the values that underpin curriculum design within a school. We all share the responsibility of designing curriculum that not only imparts knowledge but fosters a sense of belonging and inclusivity preparing our children to become global citizens. This journey begins with a deliberate and conscious approach to curriculum design. Every decision we make, from the voices we amplify to the resources we use, must reflect the diversity of human experience.

When facilitating discussions with RE subject leads on this topic, we speak about the implicit and explicit features of the curriculum. The implicit being those decisions we make as curriculum designers about what we include and represent. It means asking ourselves critical questions: What perspectives are included in our syllabi? Whose voices are being centred? Are we offering a diverse range of representation? These considerations extend beyond the mere content of our subjects; they seep into the language we use, the images we present, and the values we share. These decisions may not be explicitly obvious to the children in our lessons, but it frames a journey for them that better represents the world they are growing up in. Without this careful consideration, we can unintentionally establish an unconscious bias or reinforce stereotypes.

Alongside these implicit considerations is the explicit curriculum, where we dedicate time in lessons to directly address issues of diversity, equity, inclusion, justice, and belonging (DEIJB). It’s about more than just ticking boxes; it’s about fostering meaningful dialogue, challenging biases, and nurturing a culture of respect and understanding. SMSC subjects provide the structured opportunities for students to explore complex societal issues, interrogate their own beliefs and biases, and develop the critical thinking skills necessary to navigate an increasingly interconnected world. For staff to feel confident in leading these discussions, we need to support the ongoing development of their knowledge and understanding of these issues as well as the ways in which safe learning environments can be established, and discussion and debate can be managed. This will support them in feeling confident to plan in these explicit curriculum opportunities for our children.

This is not a small job or short conversation with a defined end point. This is ongoing work, and it should be contextual. It is important that schools support their staff to engage with this through investment in high-quality resources, providing the time and opportunity for evaluation and review, and dedicating time to ongoing learning and development for staff.

In a world dominated by technology, AI, and algorithms, education needs to do more than impart knowledge. It must nurture empathy, compassion, and a sense of collective responsibility. To achieve this, we must elevate and enhance subjects like RE and PSHE. They are essential components of a well-rounded education that prepares students to navigate the complexities of the modern world.

Reflecting on Privilege and Pupil Premium

Written by Gemma Hargraves

Gemma Hargraves is a Deputy Headteacher responsible for Safeguarding, Inclusion and Wellbeing.

I recently attended a national Pupil Premium Conference in Birmingham. The first speaker asked for people to raise their hands if they have personally experienced poverty – I have not, so I did not raise my hand. The number of people who did was striking. I was reminded of my experience at Bukky Yusuf’s session at the first Diverse Educators conference when we were asked how many boxes we tick in terms of diversity. I am very aware of my luck, my privilege, and whilst my father would have proudly proclaimed his working class roots he made sure I had a comfortable upbringing never wanted for anything.

Spending the day surrounded by educators who care deeply about supporting students and families eligible for Pupil Premium I was struck by the need to get to know these students at my school better. Since joining the school in September I know some very well, for various reasons, but others I have not met yet. Sean Harris’s keynote was compelling about rewriting the story of disadvantage in schools and communities.

We cannot assume all students in receipt of Pupil Premium funding face the same challenges. When I say “we” I mean myself, as Deputy Headteacher in charge of Pupil Premium strategy, but all teachers and staff in schools. Vital here are Form Tutors who see the students every morning and offer a caring and consistent welcome. Also, Receptionists, canteen staff, all teachers and leaders in schools. “We” here should also mean policy makers – those who decide who qualifies for Pupil Premium, and Service Pupil Premium, and who doesn’t but who also need to be supported (of course this is all students but I am especially thinking of those who are only just above the Pupil Premium qualifying line, disadvantaged sixth formers, of young careers, of others with additional needs). We must all endeavour to know these pupils as individuals and to give them opportunities to shine.

There are practical and logistical challenges of course. Schools Week this week reported that school will have to wait until May to find out their pupil premium funding allocations for 2024-25. The data was supposed to be out in March but had been hit by a ‘problem’ with identifying eligible reception pupils. This clearly makes it more challenging for schools to budget and perhaps recruit but we just not lose sight of the children affected. Similarly, when focusing on outcomes, Progress 8 or some other measure we must remember there are individual students and families behind these numbers.

Of course, our approach must be intersectional. A child is not only “Pupil Premium” they may also be a devout Muslim, disabled, a child of LGBT+ parents or indeed all or none of these but we will only know and be able to celebrate this if we get to know the pupils and families better. We must find funds to support them in ways they need, not what we assume will be generically helpful.

And while literacy is of course important and key to probably every Pupil Premium strategy, and improving educational outcomes can be transformative, we must also focus on cultivating a sense of belonging, confidence and joy. I’ve been doing a lot of work on inclusion, diversity and belonging in schools over the past few years, but this conference gave me a renewed focus on poverty and inequality. In the spirit of pledges from previous WomenEd and DiverseEd events, I am now committing to spend more time reading, thinking, and researching about poverty and inequality in my community but also, of course, getting to know the students and families so they can truly flourish.

Open-mindedness: The most important thing we can teach young people

Written by Liselle Sheard

Liselle is an experienced Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion professional, driving change in organisations of all sizes including global ftse 100 companies. Liselle is passionate about having a positive influence and encouraging others to do the same.

In a study by Mind UK (2021), 78% of young people said that school had made their mental health worse. 70% of young people who experienced racism in school said that it had negatively impacted their wellbeing. These stats are expected to increase further for minoritised young people. At such a critical age, children are internalising negative beliefs about their differences, and are questioning their place in society. Can we expect young people to achieve top grades and sail through school when the environment is excluding underrepresented groups and shaving their confidence at the very beginning of their journey into adulthood?

Complex data analysis and strategic models have a necessary place in the fight to drive systemic change, but are we overlooking the power of fundamental traits such as curiosity and open-mindedness? Can educational institutions model these traits to drive inclusion, and teach young people to follow suit?

Open-mindedness is the willingness to actively search for a diverse range of information, perspectives, and solutions when navigating through life. It’s the ability to admit that we always have more to learn, and that our experiences shape our perspectives.

In the education industry, open-mindedness can drive an inclusive environment for young people, whilst also encouraging them to be a catalyst for change themselves. In this sense, open-mindedness is about encouraging individuality whilst forging togetherness in the process.

Open-mindedness and finding identity:

Navigating the education system as a young person can bring about complex emotions. Systemically, individual differences and needs have been left out of the conversation, with a holistic service delivered in the same way to everyone. Young generations have expressed feeling stripped of their individuality and self-expression, making it difficult for students to find out who they really are, and grow confidence in their own identity.

To overcome this, self-exploration must be encouraged and welcomed wherever possible, and students should be given the power to consider what is important to them. When this culture is embedded into schools and colleges, it’s embedded into the outlook that young people have on life, increasing their respect and empathy for those around them.

An open-minded education system would fuel a culture of acknowledging the positives of our differences, giving young people the tools they need to support one another.

Open-mindedness can break down the stigma and shame attached to diversity and begin to replace this with pride. However, achieving this culture shift requires commitment from everyone, from industry bodies to individual teachers.

On one hand, it’s crucial that we take steps to increase the diversity of leaders in the education system so that representation is visible to young people during their childhood. On the other hand, we also need to be working to diversify the content covered in the curriculum so that young people are educated on different cultures and perspectives. Students should be able to learn about their own histories in school, as well as uncovering the histories of people with different identities to themselves.

Open-mindedness and finding purpose:

A wealth of research highlights the link between happiness, success, and purpose (Harvard Business Review, 2022). Rather than mapping out young people’s lives for them and pushing them to follow a rigid process, students should be taught the importance of finding their own purpose.

Young people should be supported in finding a purpose that will give meaning to whatever they do. By adopting this mindset, we can encourage students to create their own opportunities, and be ready to explore anything that comes their way.

With an open-minded outlook, young people are more likely to engage in information from a diverse range of creators, encouraging them to build connections with those who have different backgrounds to themselves, and expanding the opportunities that become available to them. Young people should be encouraged to remain curious and enjoy the journey of growing older. This journey is inevitably more educational and colourful when diversity is embraced.

Open-mindedness and its impact on others:

Being open-minded not only helps individuals to increase their understanding of the world and access opportunities, but it also helps young people to make more well-rounded and empathetic decisions that support others.

Open-minded young people bring a future of more inclusive friends, colleagues, innovators, and leaders. As the future of the planet and society becomes ever more uncertain, it’s fundamental that we support young people to build a future where everyone can thrive together.

If we look at many of the most widely recognised thought leaders across the world – from storytellers to artists, to activists – a key trait shared amongst them is their own open-mindedness, and their ability to open other minds to new ways of thinking. The most influential art, music, films, books, and speeches are those that stimulate; blurring societal boundaries and questioning norms.

As younger generations become increasingly more attached to the mission of driving wellbeing and inclusion, they themselves should be empowered in the education system to offer reverse-mentoring and share their ideas for change. Welcoming diverse young perspectives will build the confidence of students and teach them how to find their own power. Opening opportunities for students to be the ‘teachers’ would help to highlight how young people feel, where improvements can be made, and what actions can be taken to drive a more inclusive education system.

Is there a hierarchy of protected characteristics?

Written by Hannah Wilson

Founder of Diverse Educators

One of the questions we regularly ask in our DEI training for schools, colleges and trusts is which of the protected characteristics are visible within your context.

This question is deliberately wide and can be interpreted in a couple of different ways:

- Which of the 9 PCs are visible? i.e. which ones can we see as some are hidden/ invisible.

- Which of the 9 PCs are visible? i.e. which are present in our community and thereby which are missing or do we not have/ know the data to confirm they are present.

- Which of the 9 PCs are visible? i.e. which are being spoken about, invested in, have we received training on.

Often people ask do we not mean – which is a priority? And we emphasise to focus on visibility and explain the gap between intention and impact as there is likely to be some dissonance between what is happening and how it lands.

The reflections and discussions across a full staff will surface some of the disparities of what is being paid attention to. Moreover, it will also highlight the difference in perspectives across different groups of staff – groups by role/ function and groups by identity.

A key thing for us to reflect on, to discuss and to challenge ourselves to consider is that there are nine protected characteristics – so are we thinking about, talking about, paying attention to all of them simultaneously? Are we balancing our approach to create equity across the different identities? Are we taking an intersectional lens to consider who might be experiencing multiple layers of marginalisation and inequity?

We encourage schools to lean into DEI work in a holistic and in an intersectional way, as opposed to taking a single-issue approach as our identities are not that clean cut. We worry that some organisations are focusing on one protected characteristic per year, which means that some people will wait for 8-9 years for their identity to be considered and for their needs to be met. This is also a problem as we generally spend 7 years in a primary context and 7 years in a secondary context so all 9 would not be covered in everyone’s educational journey.

Trust boards, Governing bodies, Senior leader teams do not sit around the table and decide that some of the protected characteristics are more important than others, but there will be a perception from outside of these strategic meeting spaces that there is a hierarchy. i.e. different stakeholders will have differing opinions that in this school we think about/ speak about/ pay attention to/ deal with XYZ but we do not think about/ speak about/ pay attention to/ deal with ABC.

Another thing to consider about the perceived hierarchy is regarding which of the protected characteristics we are expected to log. If all 9 of the protected characteristics are equal, why do schools only need to log and report on two of them for the pupils’ behaviour and safety – we are expected to track prejudiced-based behavioural incidents of racism and homophobia? Does this mean that transphobia, islamophobia, ableism and misogyny are less important? Does this mean we are holding the student to account but not the staff?

One solution to this specific imbalance is to move from a racist log and a homophobia log to a prejudice log. A log that captures all prejudice, discrimination and hate. A log that captures all of the isms. A school can then filter the homophobia and racism to report upwards and outwards of the organisation as required, but the organisation’s data will be richer and fuller to inform patterns of behaviour and intervention needs.

CPOMs and other safeguarding and behaviour software systems enable you to tailor your fields so see what capacity yours has to add in extra fields. You can then log all prejudice and track for trends but also target the interventions. We have been working with a number of pastoral leaders and teams this year to grow their consciousness, confidence and competence in challenging language and behaviour which is not inclusive and not safe. We are supporting them in making their processes and policies more robust and more consistent to reduce prejudice-based/ identity-based harm in their schools.

Another consideration alongside the student behaviour logging and tracking is to also consider the logging of adult incidents. Do our people systems capture the behaviours e.g. microaggressions and gaslighting that the staff are enacting so that these patterns can also be explored? Do our training offers for all staff, but especially leaders and line managers empower and equip them to address these behaviours?

So as we reflect on the question: Is there a hierarchy of protected characteristics?

Consider how different people in your organisation might answer it based on their unique perspective and their own lived experience. And then go and ask them, to see how they actually respond so that you become more aware of the perception gap – if we do not know it exists, we cannot do anything about it – and the learning is in the listening after all.

The reality of being black in Durham - a diversity deficit

Written by Charlotte Rodney

As an undergraduate student currently pursuing my law degree at Durham University, I am an advocate passionate about Human Rights, hoping to propel into a career at the Bar. Public speaking, debating, and writing have always been passions of mine, placing conversation at the forefront of my passions. With a willingness to better understand intersectionality that is necessary but often lacking in educational institutions, I continue to pursue ventures that raise awareness on the topic of racial injustice. Writing for Durham's student publication, Palatinate, and immersing myself further into the legal field as a Durham University Women in Law Mentor, as well as being a mentee of a leading Professional Negligence barrister myself, I hope to always remain immersed in academic and working practicing fields.

467.

That is how many Black students there are, including those of a mixed background, who attend Durham University as of the 2020/2021 academic year. What’s more, that is 467 students out of roughly 22,000. Whilst, as a Black student myself, I am not shocked to see that only 2.3% of Durham is Black, this may seem low to others when considering that this is well below the national university average of around 8%, and the Russell Group average of 4%. What then is causing this? In conversation for a second time with the newfound community for Black women in Durham, Notes From Forgotten Women (NFFW), we have gone further into sharing the experiences of what it is like to be Black in Durham, delving to the root cause of the problem.

Co-founders of NFFW, Chloe Uzoukwu and Subomi Otunola gave their opening remarks on what their experiences have been like as Black women in Durham. Subomi discusses coming from a largely white background having studied in Bath, and how “I got to Durham and it seemed like that same cycle was going to continue where I barely had any black friends”. Subomi then goes on to describe her experience as “disheartening” being one of the only Black people in her History and Classics modules. “Even within my college, if I wasn’t placed with black people, I would not have spoken to them because the majority of my other friends and the people I’ve met within my college have been either people of colour, broadly or White.” Chloe echoes much of Subomi’s sentiment, describing her experiences growing up in Switzerland. “I would say that my experience in Durham has actually been arguably a big improvement from what I’m used to.”

…we ARE still here

One of the key points our discussion led us to was the difficulty of Black people coming together and finding one another at Durham. Chloe describes struggling in having to reach out to others of a similar background during her early time at the University. Whilst there is a general experience shared by all university students of having to reach out to others in your new environment, Chloe emphasises how other White students have the luxury of not needing to further search for people that look like them. “I actually really had to go and branch out on my own to find other Nigerian people… which is something that, you know, white people don’t necessarily have to do.” Sara Taha, NFFW’s social media manager, added her remarks on what she believes the key issues to be. Firstly, Sara highlights that “a lot of black people feel pressured to assimilate into a traditionally English culture”. Whilst Sara emphasises that this is not to say there is no place for Black people in a traditionally English culture, “the assimilation that a lot of black individuals feel they must do is at the expense of ever talking about their culture, heritage or race again”. Secondly, the discussion led us to the opposing point that in creating Black communities within Durham, with the hopes of bringing people together to share cultural experiences, this may in fact only help perpetuate stereotypes within the Black community. Sara adds, “ACS is a crucial society in many universities, just as it is in Durham…But, ACS does cater to certain people. It is usually led by a certain demographic.” What then is Durham not getting right about diversity at university, and perhaps more importantly what is going on within the student community that leads to these two polarising cultures?

Many readers might be familiar with a recent ranking that the University received via The Times, where we placed last out of 115 other institutions on the measure of social inclusion. Whilst this is an internal factor that many students may be aware of, it feels as though Durham aren’t doing enough about it. Chloe explains that “this reputation it has for not being socially inclusive, hasn’t affected them in the slightest. And if it hasn’t really affected them in the slightest, why would they care about changing?” As Sara would put it, “Durham has a certain aesthetic it has garnered over the years.” She explained that she believes that, “rather than try to seem integrated and diverse (like so many other universities), Durham values its inherent whiteness above all else.” So, with a socially exclusive culture that evidently does not prioritise Black students, what is Durham left with?

… Durham values its inherent whiteness above all else

To address the ever-metaphorical elephant in the room, it wouldn’t be fair to discuss diversity at Durham University without talking about the diversity in County Durham, and the North East as a whole. The Office for National Statistics has revealed that County Durham is 0.3% Black as of 2021. Nonetheless, the University isn’t made up entirely of students from the North East; in fact “Durham’s recruitment has not traditionally focussed on the local area, with large numbers instead coming from outside the North East”. So why is this University continuing to fall below the national average for Black students who attend university?

Durham University published their Access and Participation Plan, a 5 year plan set to conclude in the 2024/25 academic year. Within this plan, their section dedicated to all Black Asian and Ethnic Minority (BAME) students explains that Durham’s BAME proportion of all domiciled UK students remains below the UK national average because “there are geographical factors at work. Durham’s position is consistent with its regional context. The population of the North East Region is not very ethnically diverse, and this is reflected in the ethnic diversity of the NE universities…”. Furthermore, they raise the issue of having “a particular issue around the proportion of black students, which we have begun to address…” and this is a point we will return to later. For now, this is what the response has been. Sara comments that, “as a northerner, I know that there is a significant lack of black people here than down south. However we ARE still here.” Subomi added her remarks on the wider experience of what it means to be a student in higher education. “The very stereotype of what it means to be a student in the first place is to be white and to be of a certain privilege standing… we’re going to have to seek out these places to actually create a space for ourselves.” This is why, as Subomi remarks, there are no societies dedicated for white people. It is acknowledged that black students are in a minority, and hence communities are set up to facilitate a sense of belonging that doesn’t automatically exist like it does for white students. The sentiment may be there, yes, however it perpetuates a system where Black students are put in a space of being reminded they will always be disadvantaged. Afterall, you are perceived Black before you’re a student.

When asked for a comment, A Durham University spokesperson said: “We’re building a diverse, safe, respectful and inclusive environment where people feel comfortable to be themselves and flourish – no matter what their race, background, gender, or sexual orientation. “We recognise we have more progress to make in attracting black and other under-represented student groups to Durham, to ensure they feel welcome and to support their development while they are here.

“In making progress, it’s important to identify and develop solutions with our students, drawing on their lived experiences, as well as working with partners and specialist advisers. As part of this, we are consulting with student groups on the development of our new Access and Participation Plan. “We are also hoping to get a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of our racially minoritised students through our upcoming Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Survey which will open on 5 February. We encourage our students to respond so we can build as accurate a picture as possible – further details of how to get involved will be shared very shortly.”

Whilst statistics are great, and plans towards diversifying the University community may be well-intended, one can’t help but get a feeling that this isn’t an active priority for Durham University. For instance, their five year action plan “intends to add 100 UK domiciled black students by 2024/25”. That would be less than 0.5% of the student community. Sara expressed her disdain of the wording of a following paragraph which reads “Durham is not based in an area of the UK with a great deal of ethnic diversity and students with low aspirations are often unwilling to move significantly from their local area.” Sara explains that “I find the label ‘low aspirational’ to be offensive and based in racist stereotypes that black people ‘are not trying for a better future the way white people and other races are’.” What’s more, she calls for more compassion from the University in acknowledging the intersectionality of this issue.

I now call each and every reader to a point of reflection. As a Black student, would you find yourself recommending Durham University as an institution? The differing responses I have had perhaps speaks to the complexity of the issue. Chloe explains that, “I hate that we have to feel like we need to downplay ourselves simply because we’re afraid of stepping into white spaces. I don’t think that’s fair on us. And so I would 100% recommend the University to other Black students…but not without its warnings.” On the other hand Sara notes, “I am not likely to recommend Durham to fellow black students/friends, if they are used to a certain standard of diversity. First year, first term, was one of the most isolating periods in my life because my college was not diverse in any sense of the word.” What then are we left with considering the space, or lack thereof, there seems to be for Black students in Durham?

The very stereotype of what it means to be a student in the first place is to be white and to be of a certain privilege standing…

The University may have a lot to answer for in terms of tokenised efforts to add a mere 100 Black students by 2025, but the issue goes beyond that. We are immersed daily in a culture at this University where Black people are invisible. And in efforts to make us more visible, we are confined to our black spaces that very much have their own shortcomings. What might there be for us? The answer is simple: plenty. There is as much at this University for a Black student as there is for a White student, and every other ethnic background in between. Although it may not look like it, because the diversity is not fairly representative at all, we are still here and calling for the University to make more substantial efforts at diversity, beginning with tearing down the harmful association with Black students and low aspirations. So, the next time Durham University ranks comically low in what are extremely important areas of social inclusion, ask yourself who that benefits, and think of the number 467.

Black History Month: Dismantling inequalities in education for better outcomes

Written by Henry Derben

Henry Derben is the Media, PR, and Policy Manager at Action Tutoring - an education charity that supports disadvantaged young people in primary and secondary to achieve academically and to enable them to progress in education, employment, or training by partnering high-quality volunteer tutors with pupils to increase their subject knowledge, confidence and study skills.

Before the pandemic disrupted education, students from Black ethnic backgrounds had the lowest pass rate among all major ethnic groups at the GCSE level. However, the 2022-23 GCSEs marked a notable shift from the pre-pandemic period, with Black students on average achieving similar English and maths pass rates comparable to students of other ethnic groups.

Black History Month is celebrated in October each year in the UK to recognise the historic achievements and contributions of the Black community. It is also a prime moment to reflect on the state of education and how it can be reshaped to create a more equitable and inclusive future.

As part of activities to mark Black History Month at Action Tutoring, we had an insightful conversation on how to ensure better outcomes and a more enabling environment for Black pupils in schools with Hannah Wilson, a co-founder of Diverse Educators, a coach, development consultant and trainer of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion practice. Hannah’s former roles in education include head of secondary teacher training, executive headteacher, and vice-chair of a trust board.

Below are some highlights of the conversation.

Re-examining Black history in the UK curriculum

Black History Month in the UK often focuses on the celebrated figures and events in mostly Black American history, such as the civil rights movement and famous Black personalities. However, Hannah highlights an important criticism – the lack of focus on UK Black identities.

“We want to move to the point where Black culture and identity are integrated throughout the curriculum,” Hannah explains, advocating for a more inclusive and comprehensive approach. The celebration of Black identity is that it’s often a lot of Black men being spoken about and not Black women, queer people, and disabled people. Thinking about that intersectionality and looking at the complexity and the hybridity of those different parts of identity often gets overlooked as well.”

A new Pupil Experience and Wellbeing survey by Edurio shows that pupils of Any Other Ethnic Group (48%) are 21% more likely to rarely or never feel that the curriculum reflects people like them than White British/Irish Students (27%). Additionally, Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups (16%) and Black/African/Caribbean/Black British students (18%) are the least likely to feel that the curriculum reflects them very or quite often.

Unpacking performance gaps

Data has shown that while a high percentage of Black students pursue higher education, they often struggle to obtain high grades, enter prestigious universities, secure highly skilled jobs, and experience career satisfaction. The journey to understanding the root causes of these educational disparities is a complex one.

Hannah recommended the need to rethink career education and the lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion strategies that often work in isolation.

“I don’t think all schools are carefully curating the visible role models they present. The adage about if you can’t see it can’t be it, and the awareness around the navigation into those different career pathways. I think that is saying that schools could do better. There’s a bridge there to be built around the pathways we are presenting as opportunities on the horizon for young people as well. Representation within the workforce is another key aspect. We need to address the lack of Black representation in leadership positions, not only in schools but also in higher education.”

The early years and disadvantage

Disadvantage often begins at an early age. Children from low-income backgrounds, including Black children, start school at a disadvantage. Hannah pointed out that the key to dismantling this cycle lies in reimagining the curriculum, the approach to teaching, and in valuing cultural consciousness.

“It’s important to start with the curriculum. The curriculum in the early years should be diverse and inclusive. The thought leaders within that provision or within that key stage are often quite white. That’s often the disconnect at a systemic level when it comes to policymaking around provision for the early years. Who is designing the policy for the early years? Who’s designing the curriculum for the early years? Are we being intentional about representation in the early years?”

“However, we need to move beyond simply adding diversity as a “bolt-on.” Their representation should be integral to the curriculum, not an afterthought. As young as our children join the education system, what can we do differently from the get-go to think about identity representation.”

Breaking the concrete ceiling

While tutoring is a viable method to help bridge the gap for underperforming students, Hannah stressed the need to change the system fundamentally. Rather than continually implementing interventions when problems arise, it’s best to revisit the structure of the school day, the diversity of teaching staff, and the core content of the curriculum.

“It has to start with the curriculum, surely tutoring and mentoring all of those interventions like mediation support mechanisms are so powerful, we know that make up the difference. But what are we actually doing to challenge the root cause? We have to stop softball. We’re often throwing money at the problem, but not actually fixing the problems or doing things differently. We need a big disruption and conscious commitment to change, but it needs to be collective.”

“We need to address the concrete ceiling that often prevents Black pupils from accessing leadership opportunities. Career guidance, sponsorship, and mentoring should be part of the solution to break these patterns. Collective action is essential to create lasting change.”

The power of engaged parents

Change should also start at home. Parents and guardians play a crucial role in a child’s education, particularly in the early years. Hannah suggests a shift in the dynamic between schools and parents.

“Thinking about how we work with parents and create a true partnership and collaboration. That to me, is what some schools perhaps need to revisit – their kind of plans, commitment, or the ways they work with different stakeholders. Engaging parents more closely is definitely a way of helping them get involved in schools so they’re part of that change cycle.”

The call to action for allies

In conclusion, Hannah’s powerful call to action focuses on allyship, encouraging non-Black people to actively support and contribute to the ongoing struggle for equity and inclusion in education.

I think for people who identify as being white, the reflection and awareness of your own experience with schooling, where your identity is constantly being affirmed and validated because you saw yourselves in the classroom, in the teachers, in the leaders, in the governors, and in the curriculum, that’s often taken for granted. It’s time for us to step back, see those gaps, and to appreciate how that affirms us, but how that could actually really erode someone’s sense of self when they don’t see themselves in all of those different spaces.”

There should be a conscious intention that educators make about what they teach, who they teach, and how they teach it, to really think about representation and the positive impact it has on young people. And being very mindful that we don’t then just perpetuate certain stereotypes and not doing pockets of representation and pockets of validation.”

Hannah’s insights underscore the urgency of addressing the disparities in our education system. As Black History Month wraps up, let’s heed the call to action and take collective steps toward a more inclusive and empowering education system that taps and nurtures the potential of all young Black students.