A Call for Action

Written by Esther Mustamu-Daniels

Esther Mustamu-Daniels has 20 years of teaching experience working in London and the Middle East as a Class teacher, Education officer, Middle Leader and DEI Lead. Currently working at British School Muscat, Esther co-leads the DEI work across the whole school.

I read the most horrific story of a child being sexually assaulted by police in her school. Her teachers did nothing to protect her. Her parents were not called. She was strip searched while in the middle of an exam while on her menstrual cycle. She was not allowed to clean herself after. She was not checked upon to see if she was ok and then she was sent back to her exam to continue it. All by people who are supposed to protect and look after her. All I kept thinking about was what if this was my child? This happened two years ago and the conclusion of the investigation is that ‘racism was likely to have been an influencing factor’.

Unacceptable. The child is now in therapy traumatised by these events and now self harming.

What if this was your daughter? What would you do?

I have been thinking about the reports of Ukraine. How our children feel hearing these reports. Not only of the African students who have been denied entry on to trains and through borders but also of the reporting. How black and brown lives are deemed lesser and how this is normalised in our media. What impact is this having on our children? On all of them? How wars in certain countries are acceptable but in others ‘horrific’. How western media is more sympathetic towards a ‘type’ of refugee. What are we sharing with our children? With all of them? What are we teaching them? What kind of world are we showing them exists?

There are so many stories in the media that show our children the unjust and prejudiced way of the world; how can we counteract this? How can we show them that they are all important? That their lives matter? Put yourselves in their shoes and think about the messages that they are receiving. Think about what you can do to counter that.

If you are a teacher, what do you show your children? The stories and images you choose to share have a huge impact. The authors you share and the lessons you teach that include positive role models, narratives and histories will all have an impact. Are you considering the impact that current events are having on your children? What are you doing to support them? Are you calling out if you see racist or biased behaviour?

If you are a leader, what are you doing to counter these messages? Are you holding spaces for people to share and raise concerns with you? Are you actively trying to ensure that your establishment does not reinforce these messages? What policies do you have in place? What training do you have in place? If you are not aware or are not sure how to navigate these situations, are you seeking support and advice from those who do know?

This is a call for action to break these biases. Are you aware of what some of your children and colleagues may be facing? Are you aware of some of their experiences? Could you even be responsible for some of their experiences? Imagine it was you? Imagine it was your family? What would you do? What will you do? What action will you take? What will you do today to support our future generations and all of our children and adults who are impacted and continue to be impacted by the traumas they witness?

Take action for what is right in whichever area you occupy. We all have the power to take this action and make a difference so that the bias stops. So our children and our communities are safe; psychologically and physically. What will you do?

The Non-Linear Road To Recovery

Written by Bianca Chappell

Bianca Chappell is a Mental Health Strategic Lead, Cognitive Behavioural Coach and Mental Health First Aider.

When things go awry, we like to know what to do and how to do it, so that it can be sorted out – it’s a totally natural response. With some illnesses, the treatment is simple and we are able to move on. Unfortunately, mental ill health isn’t so straightforward, and to make it even more frustrating, recovery is hardly ever linear either – we don’t experience feeling better in a nice, neat, straight line.

Life is mostly unpredictable and there’s only so much that we can control. Our mental health can take a knock-back from the things which go on internally for us, but also the things which happen externally.

We may have been going along all hunky-dory and then something happens to cause one of those sinking-stomach rough patches that we work so hard to avoid. Similarly, we might have had a long murky spell and then find that something happens to give us a lift.

Our mental health isn’t stationary, it’s transient and a counter reaction of so many individual factors. It’s difficult to always know what’s helping and what’s not, to be able to make changes to rebalance and create new habits to feel settled again.

It’s hard work and sometimes we’ll put time and effort into something that isn’t quite right for us which can be demotivating and use up energy which is in limited supply. The very nature of mental ill health is that it depletes our energy resources, so we’re always having to weigh-up where we are, with where we’d like to be, but to also be mindful that we’re not using up all of our future energy supplies. It’s a never-ending puzzle.

Life in itself is full of ups and downs. When we add mental ill health to the mix, those lows can feel extraordinarily painful and crushing. We’re working so hard to move forwards, towards good health, and those setbacks can really dent our hope and confidence. We might find ourselves in a spiral of ‘well I’ve tried so hard and things are still going backwards so everything is hopeless and I’ll never get better so there’s no point in trying any more’. It can be very easy to get into this spiral and it is very hard to get out of it again. Hitting a blip doesn’t mean that everything is hopeless and it certainly doesn’t mean that all of our hard work is for nothing. When it all feels a little much, take some time out to hunker down and up the self-care. It can feel counterintuitive but energy, hope and motivation aren’t in limitless supply, we often need to stop, to take stock and top-up.

On the face of it, it often seems as though there’s no logical reason for our mental health deteriorating. But there’s usually something, however small it might seem, which has affected how we feel.

It can take a bit of work to figure out the sorts of things that might be contributing to our mental health dipping; habits, boundaries, obstacles, lack of support, triggers etc. We might need some help with identifying what our triggers are and in learning how to handle them. One of the things which can help is to keep a mood diary – this helps us to see patterns but also gives us an in-time reflection on what was what for us at any given time.

The more knowledgeable we are about our stressors, the more equipped we are to make decisions which are right for us and our mental health.

When our mood dips again, or we use behaviours we haven’t used in a while, it’s easy to feel hopeless, useless, and frustrated. We might find that we feel like nothing has changed, as if we’ve not got anywhere, and nothing is any different from last year, or the year before that, or the year before that.

Relapsing doesn’t erase our recovery. All the things we’ve achieved – keeping our mood stable for a while, going for a period of time without using behaviours, or something else – are still achievements.

When we look back, it’s the grotty and the great that we see – but the in-between stuff is just as valuable; there’s important knowledge we’ve gained and lessons we’ve learned which help us to be more informed going forward. Every time we go through a rough patch, we can take an insight from it to aid our recovery. Even though it might not feel like it, we will be in a different place from the time(s) before. We have more experiences and more skills than we’ve had in the past. We never go right back to square one because we’re approaching each rough patch from a slightly different place.

Mental ill health isn’t something we’d choose and it’s definitely not a stick with which to beat ourselves up about. We didn’t choose to be mentally ill in the same way that we don’t choose to catch a cold. When we punish ourselves for how we feel, it makes us feel worse and plays into the hands of the illness we so want to be free from.

Not being okay can be hard to cope with, we so desperately want to be okay, but it is okay not to be okay. Nobody can be okay all of the time and recovery will always be full of ups and downs as we learn new things. It’s when we own-up to our not-okay-ness that we find ourselves in a place more accepting of help, more likely to ask for help, and more open to changes, self-care and being gentler to ourselves.

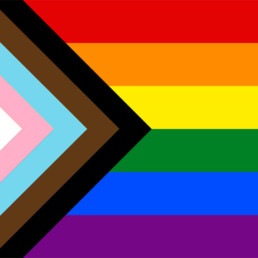

How East Stanley Primary School used Rainbow Laces to build a more inclusive environment for its pupils

Written by Adam Walker

Adam is a Primary Teacher at East Stanley Primary School in Durham and is a member and advocate of the LGBTQ+ community.

‘The number one thing is the inclusivity benefits of the resources. Not having pupils question who is playing football and building a much deeper level of respect for each other.’

Creating an inclusive environment for pupils is a top priority for many teachers and their schools. As we celebrate LGBTQ+ History Month, Adam Walker, a teacher from East Stanley Primary school tells us about how using the Rainbow Laces resources, from Premier League Primary Stars, helped create a more inclusive environment for his pupils – increasing their understanding of gender stereotypes and the LGBTQ+ community.

“We had an incident at a football match a few years ago where a pupil from our school called a player from another team a homophobic slur. It was at this point we realised that we needed a solution that we could use to support our pupils in understanding the importance of being inclusive. After a long search to find the right solution, we came across the Rainbow Laces resources from Premier League Primary Stars. A bank of free resources that could educate our pupils around the importance of inclusivity, challenging stereotypes and being a good ally – it was exactly what we were looking for.

At East Stanley we are seeing more girls wanting to get involved in sport. So it was great to see Premier League Primary Stars use male and female professionals in their resources to show balanced representation of real sport. Activities such as ‘Do it like a…’ and ‘Be an ally’ have been popular with the pupils. It has especially given the girls something to look up to and through challenging stereotypes we have mixed teams playing football with a deep level of respect for each other.”

East Stanley has used the Rainbow Laces resources in PSHE lessons at the school to create a more open environment: “The Rainbow Laces resource pack helped us in our PSHE lessons when talking about what it means to be a part of the LGBTQ+ community or discussing gender stereotypes. Now all the pupils are aware of different types of representation; they know that it doesn’t matter if you are homosexual or heterosexual, a boy or a girl, your ethnic descent, or what your first language may be.”

As a member of the LGBTQ+ community, Adam appreciates the difference that resources like Rainbow Laces make: “Now that I have these resources I reflect and think that if material like this had been available when I was in school, it would have helped me to identify and feel more comfortable as a result of inclusive topics being spoken about openly. The more we use material like this in primary schools, the more we will create a better environment for everybody to live freely. It is only going to have a positive influence.”

Speaking about whether he would recommend the resources to fellow teachers, Adam said: “I would 100% recommend them. Knowing how the PSHE curriculum works, Rainbow Laces has been great for us. For other teachers who are looking to increase inclusivity at their school, we have loved the outcomes the resources have given us. Premier League Primary Stars has a wide variety of resources too and there is also the opportunity to build Rainbow Laces – and others resources – into additional lessons around Maths, English and PE. We have seen a real difference and our pupils are happier as a result.”

At the end of 2021 and during the Premier League’s Rainbow Laces campaign, Premier League Primary Stars launched a new resource pack called ‘Rainbow Laces – This is everyone’s game’. The pack, perfect to build into PSHE lessons this LGTBTQ History Month, includes an educational film, and supporting resources, celebrating LGBTQ+ football fans and showcases the power of football to bring people together. The film tells the story of a young Sheffield United fan and member of the LGBTQ+ community, who talks about what football means to her and how it has played a part in helping her to feel proud of who she is.

Premier League Primary Stars has a wealth of dedicated LGBTQ+ and Anti-Discrimination resources – all free – for teacher to use in the classroom linked to English, Maths, PE and PSHE here.

About Premier League Primary Stars

Premier League Primary Stars is a national primary school programme that uses the appeal of the Premier League and professional football clubs to inspire children to learn, be active and develop important life skills. Clubs provide in-school support to teachers, delivering educational sessions to schools in their communities. Free teaching materials ensure the rounded programme, which covers everything from PE and maths to resilience and teamwork, is available to every primary school in England and Wales.

The Premier League currently funds 105 Premier League, English Football League and National League clubs in England and Wales to provide in-school support for teachers.

For more information about Premier League Primary Stars or to register, visit: www.plprimarystars.com

You can also contact Ben Lewis-D’Anna on blewisdanna@everfi.com or 07590465455.

Anti-bullying beyond Anti-Bullying Week

Written by Hannah Glossop

Head of Safeguarding at Judicium Education. Previously a Designated Safeguarding Lead and Assistant Head, Hannah now leads audits and delivers training to support schools with all aspects of their safeguarding.

2021 was yet another year where we saw a raft of deeply worrying examples of bullying. Research from the Anti-Bullying Alliance highlights that bullying continues to play a big part in young people’s lives: “Data we collected from pupil questionnaires completed between September 2020 and March 2021 also showed that one in five (21%) pupils in England report being bullied a lot or always.” High profile cases such as the institutional racism within the cricket world show that bullying in relation to our nine protected characteristics is a problem that goes far beyond schools.

Anti-Bullying Week 2021 brought with it a range of wonderful resources, tweets and articles in relation to anti-bullying back in November. As we march through the academic year, it is essential that we do not lose momentum and that we pay particular attention to tackling any bullying related to protected characteristics. So how can you do this?

1.Involve your pupils.

Consider an anonymous survey of your pupils, asking how many have witnessed bullying at school. This will give you a much clearer picture of how much is going on at your school and which groups are particularly targeted. Show students that you are taking bullying seriously and involve them in the policy decisions. Create a version of the bullying policy that is accessible for younger pupils.

2.Embed a culture of vigilance.

Empower both staff and students to act when they see or hear bullying taking place, either in person or online. Review the ways in which bullying is reported at your school-will all staff know how to progress bullying disclosures? Do students recognise that many nasty remarks may violate the Equality Act? Do students have a way to report bullying which avoids them having to speak face-to-face to a member of staff? Promote your anti-bullying work around the school, share it online and tell parents and carers. If pupils know you are taking it seriously, they are more likely to report it.

3.Identify hotspots.

Identify any particular areas in school, times of the day or online platforms where bullying seems to be taking place more frequently. Where possible, increase supervision in worrying areas or at problematic times of the day. If much of your reported bullying is taking place online, use external resources such as your Safer Schools Officer to explain when online abuse crosses a line and becomes illegal activity-for example hate crime and blackmail.

4.Curriculum.

Educate young people around the protected characteristics, what the Equality Act means and what impact this Act has on everyday life. Ofsted have recently updated their guidance on ‘Inspecting teaching of the protected characteristics in schools,’ noting that “No matter what type of school they attend, it is important that all children gain an understanding of the world they are growing up in, and learn how to live alongside, and show respect for, a diverse range of people.” In addition, the Proposed changes to Keeping Children Safe in Education 2022 include a new section on schools’ obligations under the Equality Act 2020, adding schools, “should carefully consider how they are supporting their pupils and students with regard to particular protected characteristics – including sex, sexual orientation, gender reassignment and race.”

5.Record and review.

Paragraph 78 of the Ofsted’s School Inspection Handbook lists the “Information that schools must provide by 8am on the day of inspection” and includes:

- “Records and analysis of bullying, discriminatory and prejudiced behaviour, either directly or indirectly, including racist, sexist, disability and homophobic/biphobic/transphobic bullying, use of derogatory language and racist incidents.”

Rather than seeing this as a mere Ofsted “tick box” exercise, use these records to fully explore which forms of bullying are happening within and around your school. Ensure that each reported bullying instance is recorded, using your behaviour management or safeguarding reporting mechanisms. Investigate any trends in these reports, share these with governors and senior leaders and take meaningful action to address these. For example, if disability-related bullying is becoming prevalent, think about what resources are needed to both educate children and show them that this form of abuse will not be tolerated.

Over the coming months ahead of the next annual Anti-Bullying Week, bear the above in mind and remember that embedding some of these ideas could make many of your students feel much less segregated from school life and much more likely to thrive.

Belonging, safely

Written by Gemma Hargraves

Gemma Hargraves is a Deputy Headteacher responsible for Safeguarding, Inclusion and Wellbeing.

Reflecting on several sessions from the recent Diverse Educators virtual conference it struck me that so much of our EDI work is also vital safeguarding work. As a Deputy DSL I spend my days balancing pastoral care, safeguarding, History teaching and various other responsibilities. Until now I actually hadn’t realised how my EDI work is complementary to my safeguarding work.

All readers will have heard that “you can’t be what you can’t see” and this need for recognition and role models extends to safeguarding too. Pupils need to know they are in an environment where they are valued and celebrated in order to feel truly safe. It strikes me that a pupil may not disclose various issues if they feel they would not be heard, understood or believed. Beit a neurodiverse pupil struggling with issues around consent, an LBGTQ+ young person experiencing unkindness, a disabled child faced with ableism daily or a person of colour dealing with regular microaggressions. Of course having a diverse staff body, including in senior positions, may help ensure all pupils feel safe and a sense of belonging but active allies have a vital role to play here. Pupils in the first presentation said “ignorance breeds intolerance” and I would build on that to say in safeguarding terms ignorance is dangerous. We all need to be professionally curious whilst being respectful. @AspringHeads gave some examples of shocking things Black teachers have been asked, including endless comments about hair, skin colour or names, and comments of this nature to Black pupils would absolutely be considered a safeguarding concern.

A key part of safeguarding is also accurate and timely recording of incidents; this is key to tracking trends and understanding context to actively promote inclusion. If we are to ensure all pupils are safe and can thrive, we need to have a clear picture of incidents or challenges faced. We have a duty to ensure that pupils are not negatively labelled or stereotyped based on any characteristic and teachers have high expectations of all pupils. Safeguarding is also about preventing harm to children’s development and taking action to enable all children and young people to have the best outcomes – here EDI is clearly vital and we can see tangible returns on investment in diversifying the curriculum. Of course, we reinforce this by the displays around school, the books studied, the trips that are offered etc but the culture individual teachers nurture in their classrooms is key to both EDI and safeguarding.

As was made clear at Diverse Educators recently, good intentions are not enough. We must act. EDI requires resourcing, time and energy. It must not be an afterthought in another year of TAGs marking and administration, staffing issues and COVID challenges ad infinitum. Safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility and so is EDI. We need to recognise and respect cultures, traditions and changes but with clear red lines in terms of safeguarding to ensure everyone can bring their whole self to school and be safe. Sometimes we hear “I don’t see colour” but surely we must see it, value it, celebrate it and protect all children regardless.

The Heterosexual Matrix

Written by Dr Adam Brett

Adam has completed a doctorate exploring the experiences of LGBT+ secondary teachers. A presentation of his findings can be found here. He also co-hosts a podcast called Pride and Progress, @PrideProgress, which amplifies the voices of LGBT+ educators, activists and allies.

“Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay”

– Margaret Thatcher, October 1987.

Thanks for that, Margaret. You and your government created a culture of fear, silence and moral panic surrounding LGBT+ lives that continues to this day. Your speech continued, that “all of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life – yes, cheated!”.

She was right about one thing. Section 28 meant children were being cheated of a sound start in life.

Section 28 cemented schools as heteronormative spaces, where being heterosexual and cisgender were silently assumed, leaving LGBT+ people with the impossible decision or whether to be invisible or hyper-visible.

What a choice to have to make.

Do I hide my authentic self to fit in with the legislated normativity of schools, or do I make myself visible and put myself at professional and personal risk?

Patai (1992) refers to this form of hyper-visibility as ‘surplus visibility’, where a person is ‘extrapolated from part to whole’ and seen to represent the entirety of a minority group.

You might be thinking that a lot has changed since the repeal of Section 28 nearly 20 years ago in England. It’s true, a lot has changed and there has been significant cultural and legislative improvements for LGBT+ people. However, schools remain stubbornly heteronormative and cisnormative environments.

Think about the aspects of school that are predicated on a static, binary gender. Toilets; changing rooms; sports; gendered language; uniform; seating plans; residentials. The list goes on. What does this communicate for those who cannot or will not fit into the neat binary of male or female? That they don’t belong.

We could consider similar examples about the ways in which heteronormativity is maintained as the social order in schools. The curriculum; ethos; culture; policies; microaggressions; homophobia; the hidden curriculum; role models.

We can conceptualise all these examples as code.

I love to use the film The Matrix as a metaphor to explain the ways in which socially constructed ideas such as heteronormativity are held in place. When we are plugged into the matrix, we believe it’s real and can’t see the code that is continually constructing it. We can’t imagine alternatives as it’s all there is, in the same way that we can’t think outside of language.

However, when we develop the critical awareness of what is upholding this normativity and develop a language to name it, we become unplugged. LGBT+ people have the critical awareness to identify the ways in which schools seek to include or exclude them. Section 28 plugged us into a matrix of understanding where the silent assumption of cisgendered heterosexuality was so entrenched, that to this day, being an LGBT+ person in school can be a point of constant navigation and information management. Exhausting.

As educators and leaders, we need to listen to the lived experiences of our LGBT+ students and colleagues to create a culture, curriculum and language which can disrupt this code. We need to name things as heteronormative; we need to name things as cisnormative; we need to name things as microaggressions. We need a new language: one that allows us to think outside of the current heterosexual matrix. We need to create schools and spaces where LGBT+ people feel safe and included, without attracting surplus visibility.

Section 28 cheated a whole generation of LGBT+ young people out of a sound start in life. It’s time to unplug the matrix and make sure it doesn’t happen to the next generation.

Adam Brett

@DrAdamBrett

#HonestyAboutEditing - The Campaign

Written by Suzanne Samaka

Suzanne Samaka is a 33-year-old mum from Watford. She grew up in a single parent, working class family, which has given her a strong sense of working hard to achieve. She has spent 15 years working for a high street bank in a number of roles, mainly around relationships and people.

How can I make a difference to the mental health of our young people? That was my question and it hit me like a lightning bolt one evening. To give some context to my life, I am a stepmother to four children, have a two year old daughter and have recently given birth to my second baby. I also work full time in banking.

Sadly, for the past four years a member of our family has suffered with anorexia. It is fair to say we will never know the root cause of this and maybe neither will they, but it is apparent that they are not alone in the anxiety, depression, physical and mental health challenges that they have faced in their adolescent years. I’ve been to eating disorder in-patient clinics and I have always been shocked and saddened by how full these units are with adolescent girls and boys alike.

The pandemic has meant young people have spent more time at home and online but I must stress this isn’t only a post-pandemic problem. They are seeing more content than ever that is edited or filtered and it is having a disastrous effect on their self-esteem. The statistics don’t lie and in the UK, 9 out of every 10 girls with low body esteem, put their health at risk by not seeing a doctor or by skipping meals. A survey conducted by the Royal Society for Public Health asked 14-24 year olds in the UK how social media platforms impacted their health and well-being. The survey results found that Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram were all linked to increased feelings of depression, anxiety, poor body image and loneliness. More than two thirds (68%) of young people surveyed support social media platforms highlighting when a photo has been manipulated.

I have been contacted by many teachers who have told me about conversations with their students who feel under pressure from social media perfection or crippling loneliness when they feel that their face doesn’t fit. I have also been contacted by countless parents who are terrified of how body conscious their children are, with ages starting from as young as 8. I have also spoken with many adults who have suffered their own mental health challenges in their adolescent years, signing the petition because they just can’t fathom how they would have survived against the odds that the youth of today are growing up with. The more people I speak to about the petition, the more it makes me want to ensure there is change, protection and honesty to give our young people a fair chance in today’s world.

Now there is one thing I need to make crystal clear. I have nothing against social media. In fact I think it can be hugely positive to all of our lives. I also have nothing against editing or filtering, it is completely each to their own. What I have a problem with is the lack of honesty, which is causing young people to believe they need to be flawless yet striving for this is damaging their mental health. Do I believe social media is the problem for the challenges in youth mental health? No. Does it exacerbate the problem? Absolutely. Mental health challenges can quickly become deeply rooted and leave scars for life. Our children and young people deserve better than that.

In trying to evoke change I have recently begun a petition on Change.org to amend the social media laws to state when an image has been filtered or digitally edited. This is now the law in a number of countries, Norway being the most recent. If it can happen there why not in the UK? What I am hoping this solution could do is to help our young people and next generation to understand that these posts aren’t real and their true self is more important, as well as their mental and physical health.

What I have realised is that each individual can help create positive change. It really does only take 30 seconds to put your name against the petition and then share with your own network. The momentum of this campaign has been amazing with several MPs on board, charity organisations and individuals who are experts in their fields. Collaboration is key here. If we all pull together we really can protect our next generation. I’m a parent. An auntie. A person who cares. That is all it takes. Somebody to do something.

Whilst my family has been my first hand experiences of mental health challenges in young people, I have just seen one too many examples to not do something about it. In the words of Emma Watson, If not me, who? If not now, when?

The link to the campaign is https://www.change.org/ChangeSocialMediaLaws

The link to the details of the survey completed by the Royal Society for Public Health is available here https://www.rsph.org.uk/static/uploaded/d125b27c-0b62-41c5-a2c0155a8887cd01.pdf

You can connect with the author – Suzanne Samaka via the following social media accounts:

- Instagram – @protectyouthmentalhealth

- Twitter – @SuzanneSamaka

- #HonestyAboutEditing

Increasingly Visible: Being an ‘Out’ LGBTQ+ Educator

Written by Vickie Merrick

PE and History Teacher at an International School in Rome and has previously taught in Vietnam and the UK.

This post was very much inspired by Dr Adam Brett’s (@DrAdamBrett) recent talk about his PhD findings on what it means to be a visible LGBT+ educator. It is a personal reflection of my journey to becoming visible in an international teaching community.

During my ITT year there wasn’t the same talk and work that there is now about DEI, social justice and decolonising the curriculum. As a white British cis woman going through my training year, I never thought about the importance of representation. “If you can see it, you can be it” wasn’t a phrase that ever crossed my mind.

Now I realise and acknowledge that I have white privilege, I’m cisgender, I’m middle class (in that whilst my parents consider themselves working class, I went to a grammar school, I’ve gone to university twice and am currently back again completing an MSc and these experiences have afforded me the opportunity to emigrate and continue my career abroad) and I was lucky enough to be born in the Global North. There are many things about my life that mean I have an easier time than so many people in the world.

I’m also a member of the LGBTQ+ community. And I have a chronic health condition that impacts both my physical and mental health. These two areas are the only parts of my life where I have ever faced any difficulty due to my identity.

Section 28 left a strange underlying legacy on schools in England. Although I began working in schools a long time after its 2003 repeal, I heard “don’t tell the students about your personal life, it’s none of their business who you are” more than once in the staffroom. Even though my straight colleagues would quite openly talk about their partners/spouses, the insinuation was that I shouldn’t allude to being a gay woman in front of my classes.

In addition I was aware of the cultural background of my students and knew that some may not have heard positive things (or anything at all) about LGBTQ+ people at home. If I was in the same situation now I don’t think I would hide myself at the risk of causing offence (offence after all is taken not given) and would have used it as an educational opportunity to discuss embracing others regardless of their identity. But I was a new teacher concentrating on learning how to teach (something I’m still learning) and was not too concerned with being a representative of the LGBTQ+ community.

There were students who found out that I was gay and I never encountered any problems from them, if anything they were extremely positive and open about wanting to support LGBTQ+ people. On the other hand, I did once experience a student using ‘gay’ and ‘f**’ as an insult to another student in a lesson I was covering so I followed the school policy and the student waited outside for an on call member of staff. The member of staff had a chat with me and the student then brushed off the incident and sent the student back into the lesson. Again, looking back, as a more experienced teacher, I wouldn’t have let it slide. But as an NQT, I didn’t feel that I had any power to insist that this was homophobic language and should be treated in a serious way that shows the student it is not acceptable.

The final reason that I was never fully visible in my first school was more of an internal one. I teach history and PE. We’ve all heard of and perpetuated (myself included when I was a kid at school) the stereotype of the lesbian PE teacher. I didn’t want to be a stereotype. I’d previously been in the Army Reserves for a short time and found the same stereotype about female soldiers. That wasn’t my reason for leaving the Reserves but with the Army, working in sport, and being a PE teacher, it can get tiring constantly laughing with and brushing off people making jokes and having ‘banter’ about a part of who you are. And of course you laugh because they’re your colleagues and friends. They mean no harm but it’s the microaggressions that we know now to be aware of alongside our own unconscious biases that can build up and deeply impact people.

Leaving the U.K. and yearly visits to Pride Parades behind brought a change to my level of visibility. I left the U.K. with my partner and moved to Vietnam. Throughout the recruitment process we were up front about applying as a couple and didn’t face any problems when it came to contracts, housing allowances and dealing with HR in our new country. There was a surprising moment when the estate agent who was sorting out our rental apartment said the landlady was concerned that two single western women would have lots of men visiting and would receive complaints. The estate agent luckily had read the situation well and assured the landlady that she didn’t have to worry about frequent male visitors staying over…

In school itself it was a different story. We often talk about walking into our school and seeing a rainbow painted on one of the corridor walls with the words “love is love” below it. Talk about a welcoming sign. Again, at the beginning I didn’t intentionally come out to any of my students. Not through a conscious choice but I still didn’t really consider the positive impact it could have for LGBTQ+ students to see a visibly LGBTQ+ member of staff. There were other LGBTQ+ staff and couples at the school and openly LGBTQ+ students who felt they could be ‘out’ at school even if they couldn’t be at home due to the traditional values of their families. Over time, and partly due to the nature of international schools, many of the students my partner and I taught learnt that we were a couple- and exactly as it should be, they treated this as a total non-event. They treated us the same as the other teaching couples in the school. My form, however, were so excited on the day they noticed my engagement ring that I had to usher them out of the door to be on time for their first lessons because they wanted to stop and hear the full story of the proposal. And as we were getting ready to leave and say our final goodbyes in the midst of a lockdown and online learning, some of our grade 10 students were insisting that we sent wedding photos to one of our colleagues after the holidays so that they could see our dresses and hair and make-up.

In Vietnam, my visibility as an LGBTQ+ educator had increased because I felt supported by my colleagues, the school and the students. And the more visible myself and other LGBTQ+ educators were, the more I noticed the way the vast majority of our students, even though they were from all over the globe with different cultures, beliefs, values and backgrounds, treated their LGBTQ+ peers with an awareness, a kindness and acceptance. I left that school thinking that the kids are alright.

The transition into our second (well my third, as I had taught at two different schools in Vietnam) international school was where the first real challenges of being an ‘out’ educator were posed. And they were not posed by students. Recruitment during COVID was a struggle. We sent off around 40 applications and did about 15 interviews between us. We had been lucky to get jobs in Vietnam for our first international roles as it became quickly apparent that many other places were not as keen on hiring an LGBTQ+ teaching couple. Sometimes this was due to visa complications or job openings, other times it was the laws of the country (43 jurisdictions still criminalise lesbianism) and laws around housing. After a particularly challenging experience where we had offers rescinded because, after checking, the school decided their community wasn’t ready for an LGBTQ+ couple, we were feeling pretty disheartened.

Many of the schools we were applying to were IB schools. I still struggle to see how the IB, who preach about global communities and international mindedness, can promote schools and allow them to teach the IB programs when the school communities themselves are anti-inclusion.

Nearing the end of our tether with the recruitment process, my partner had an interview with a small school in Italy. Whilst they did not have a role for me, they were willing to make something part time if my partner was offered the job. The interview was a breath of fresh air. They were the first school who had asked about my partner or I as people and wanted to get an idea of us to find out how we’d fit into their community. They were upfront about wanting LGBTQ+ staff as they were aware that they had students who were part of the LGBTQ+ community and they didn’t always see themselves represented in the staff body. After accepting the jobs, my (now) wife was asked about joining the DEI team, and whilst she is careful as she knows this has become or can have the potential to be quite tokenistic in some schools, she is aware that she has the ability to do work with her team members around social justice and to help combat racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism and other forms of discrimination within our school community.

For the first time in a school, as an educator, I have been a visible member of the LGBTQ+ community from the beginning. I am aware that I have a-sexual, transgender and non-binary students (and probably others who identify as somewhere on the gender/sexuality spectrum) and delight when they come to tell me about the first time they went to a pride parade or show me the rainbow item of clothing they have worn that day. Whilst I cannot know or understand all of their experiences, especially as a cisgender woman, I can be an empathetic listener from the large umbrella family that is LGBTQ+. The school has an LGBTQ+ club run by a member of staff who is an ally to the LGBTQ+ community and who knows that providing an inclusive space for our students is everyone’s responsibility. The community isn’t perfect and the country, with its strong religious affiliations, has laws against gay couples adopting. It is a work in progress in our school that will require buy-in from all its members to fully promote inclusivity and celebrate diversity, no matter what that looks like. But it is not tiring to be visible here. Every day when I tie up my rainbow laces (a great campaign from @Stonewall) I know the importance of showing my students that LGBTQ+ people are a part of their community, we’re here to stay and that’s very much ok.

Section 28 is still hanging over us – but you don’t have to be a LGBT+ expert to make your school inclusive

Written by Dominic Arnall

Chief Executive of Just Like Us, the LGBT+ young people's charity.

One in five (17%) teachers in the UK are uncomfortable discussing LGBT+ topics with their pupils, our new research at Just Like Us has found.

It may have been 18 years since Section 28 was repealed in England and Wales but clearly things have not changed as much as we like to think. Growing up LGBT+ is still unacceptably tough, as a result, and huge challenges also remain for LGBT+ school staff who are often afraid to come out in their workplace or to pupils.

Just Like Us’ latest research also found that only a third (29%) of teachers are ‘completely comfortable’ talking about lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans topics in the classroom, despite government guidance of course reinforcing the need to include LGBT+ topics.

We found that primary school teachers are even less comfortable with discussing LGBT+ topics at school, with 19% saying they are uncomfortable and only 25% ‘completely comfortable’, despite OFSTED requiring primary schools to include different types of families – such as same-sex parents – in lessons.

The survey, commissioned by Just Like Us – the LGBT+ young people’s charity – and carried out independently by Teacher Tapp surveyed 6,179 primary and secondary school teachers across the UK. So we know this is sadly not an anomaly.

Why does this matter? Well Just Like Us’ report Growing Up LGBT+ found that having positive messaging about LGBT+ people in schools is linked to all students having better mental health and feeling safer – regardless of whether they’re LGBT+ or not. The evidence is there: LGBT+ inclusion in schools really is beneficial for everyone’s wellbeing.

When so many teachers say they’re uncomfortable discussing LGBT+ topics, such as mentioning that some families have lesbian mums, this has serious knock-on effects for LGBT+ young people’s wellbeing and mental health, who are currently twice as likely to be bullied and have depression. Having silence around LGBT+ topics only results in shame, stigma and students feeling that they don’t belong in school.

We don’t blame teachers for feeling uncomfortable. Some school staff simply may not have had the resources or personal life experiences – but all you need is a willingness to support your pupils and Just Like Us can help provide lesson plans, assemblies, talks and training so that you feel confident discussing LGBT+ topics with your pupils.

It’s also essential that we get the message out that teachers don’t need to be experts on LGBT+ topics to support their LGBT+ pupils.

You also don’t need to be LGBT+. Often we see in schools that this vital inclusion work falls to staff who are LGBT+ themselves rather than all school staff taking on the responsibility of making their school a safe, happy and welcoming place for all of their young people. This work doesn’t need to be done by LGBT+ staff – in fact, how amazing is it for students to see adults in their lives being proactive allies?

One incredible teacher, who is an ally, and a brilliant example of this is Zahara Chowdhury, who teaches at Beaconsfield High and the Beaconsfield School, in Buckinghamshire. She says it’s a “human responsibility” to include LGBT+ topics in the classroom and has been the driving force behind School Diversity Week celebrations at her schools.

It all starts with a willingness to support your students or simply diversify your lessons using our free resources – sign up for School Diversity Week and you’ll get a digital pack of everything you need to kickstart inclusion at your school.

Already doing this work? Let a colleague or fellow educator at another school know by sharing this blog – the more we share resources and reassure staff that you don’t need to be LGBT+ nor an expert, the sooner and better we can ensure all young people feel safer and happier in school.

Men, women and the rest of us: a brief guide to making university classrooms more accessible to trans and gender non-conforming students

Written by Kit Heyam and Onni Gust

Onni Gust: Associate Professor of History, University of Nottingham. Author of Unhomely Empire: Whiteness and Belonging, c.1760-1830.Kit Heyam: Lecturer in Medieval and Early Modern Studies at Queen Mary, University of London, freelance trans awareness trainer, and queer public history activist.

This is a guide for academic teachers who want to get the best out of their trans and gender non-conforming students, and to ensure that they can fully participate in the classroom and in their studies.

1. Avoid making assumptions

Don’t assume you know a student’s gender based on body-type, voice or even dress. If they do disclose their trans status, don’t assume that they have or will undergo any form of medical transition; ask them how you can support them. All you really need to know is how to address them.

2. Names and pronouns are all you need

Names and pronouns are all you really need to know from your students. For trans and gender non-conforming students, the name, sex or title on their student record may be wrong. Using a student’s ‘old’ name may force them to come out, which can be incredibly distressing as well as violating the Equality Act. To avoid this:

Names:

- Instead of calling out the register, ask students to either write or say their names.

- Be up-front with students and ask them to see you, or email you, after class if for any reason their name has changed.

- Online platforms often automatically display names from University records. Familiarise yourself with your university’s name-changing processes – and if there aren’t any, insist that they be put in place.

Pronouns:

- Even if you think it’s obvious, explain to students how you like to be addressed. This models the process for all students and makes it much easier for trans and gender non-conforming students to state their own pronouns. Regardless of whether you’re trans or not, it also sends a powerful signal, showing you’re aware you can’t tell someone’s gender just from looking at them.

- If you ask students to introduce themselves to the class, give them the opportunity, but not the obligation, to include their pronouns.

- Gender-neutral pronouns, which some students will use, include the singular they/them/their; ze/hir/hirs; fae/faer/faers. The list is growing: if you’re unsure, ask the student to model the usage for you, or research it online.

- If you get a student’s pronoun wrong, apologise, correct yourself and move on.

3. What if other students constantly misgender a student in your class?

If a trans or gender non-conforming student brings this to your attention, it may be worth taking that student aside and talking to them. If, as a transgender teacher, I suspect that this is active transphobia, I would probably ask a cisgender colleague to intervene.

4. How else can I make learning more inclusive?

Consider your syllabus. It may be necessary to teach material that uses outdated/pejorative language, or ideas, about gender and sexuality (and/or race, class and disability). Flag up the problems, explain to your students why these texts are necessary to engage with, but make it clear that you do not support these ideas and that you invite critique.

Think about how you’ll manage any resulting questions or disagreements. How can you help your students to create a trans-inclusive seminar environment without making them feel overwhelmed, alienated or defensive?

5. Pastoral care for trans and gender non-conforming students

Awareness of trans and gender non-conforming identities is moving at a fast, but very uneven, pace. While your students will hopefully have support at home and at university, that’s still not the case for the majority. In a recent UCAS report, 17% of trans university applicants reported having had a bad experience at school or college, and trans applicants were less likely than LGB applicants to have good expectations for university. The report recommends that universities and colleges introduce bespoke resources to support trans students.

Trans people remain disproportionately affected by mental health problems.If your trans and gender non-conforming students disclose mental health problems to you, treat them as you would any other student, butbear in mind the following:

- Not enough counselors or GPs are trans-aware; some have been known to do more harm than good.

- Specialist gender services have waiting lists of over two years from referral by a GP.

If a student comes out to you as trans part-way through a semester:

- Think about your reaction: this is a vulnerable moment for the student. If you don’t understand something, ask politely and calmly for clarification.

- Don’t make any assumptions: trans people differ in their identities and their choices about social and/or medical transition.

- Let the student take the lead: support them if they want to come out to their class, but don’t force it.

Further resources:

For you:

UCAS, Next steps: What is the experience of LGBT+ students in education?

Equality Challenge Unit, Trans staff and students in HE and colleges: improving experiences

For trans and gender-nonconforming students:

GIRES (Gender Identity Research & Education Society – including a directory of support groups)