Aspiring Heads Leadership Summit Conference 2021

Written by Javay Welter

NPQ, MSc, Outstanding MFL teacher, public speaker, mentor and linguist.

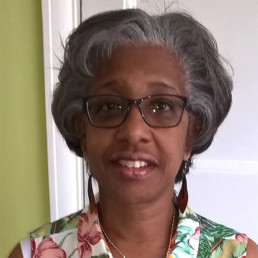

On the 16th of October, I witnessed greatness. The Aspiring Heads Leadership Summit was phenomenal. Nadine and Ethan Bernard hosted a truly remarkable conference. Above all, this was the first leadership conference I had witnessed led by a current existing Black Headteacher, Nadine Bernard. Well done Nadine for your initiative, creating this platform and elevating future leaders. This was a pioneering conference, very timely and extremely forward-thinking.

The wide array of speakers in different fields provided a variety of perspectives and insights. Topics ranged from mentoring, strategic leadership to financial literacy. The speakers were all leaders and thought leaders in their respective fields. They shared their journey, resilience and barriers they had to overcome. The optional workshops were uplifting, insightful and edifying. I left feeling empowered, inspired and acquired so much wisdom.

The first keynote speaker Bose Onaboye, who is a business strategist and leader, spoke about finding your leadership style and being highly reflective. Leadership development is a process. She encapsulated that leadership is a journey and not a destination. Leaders are readers. Therefore, one must strive to keep developing oneself and undertake CPDs. I fully agree that leading is a journey, not just a title. We must strive for excellence.

Another charismatic speaker Karl Pupé, an educator and author, highlighted that we must step out of our comfort zone to grow. Leadership is not easy and we must embrace change to grow. We must embrace more black leaders in all walks of life and value their unique and valuable skill sets and contributions. He mentioned that his various previous jobs have helped to strengthen his behaviour management, for example, negotiation, conflict resolution and dealing with challenging behaviour. His book Action Hero Teacher: Classroom Management Made Simple is an exemplary book on behaviour management. A must-read for new teachers.

Diana Osagie, a former black Headteacher and CEO of Courageous Leadership focused on being a human first and a leader second. Well-being is key to longevity. If you do not have health, you cannot lead. Sayce Holmes Lewis, Founder and CEO of Mentivity advocated that we need more servant leaders rather than being ego-centric ones to promote positive change. We need to lead from the back like Nelson Mandela. Sayce passionately highlighted that positive black male role models are crucial and that Devon Hanson, a former black Headteacher acted as an inspiration. Lavinya Stennett, founder and CEO of the Black Curriculum pointed out that Black History should be incorporated in the national curriculum and that representation is vital to success.

The second keynote speaker, Dr Leroy Logan MBE who is a former Metropolitan Police superintendent. He was also the chair of the National Black Police Association and discussed fear. He eloquently commented that his father feared his career choice. His father suffered police brutality. However, he had seen black role models and police officers in Jamaica which inspired him and it was his calling. Leroy emphasised that he entered the police profession to make a positive contribution and to help change the Met. His book ‘Closing Ranks’ shares his incredible journey from humble beginnings to becoming one the first black police superintendent in the UK. Leroy faced many adversities, barriers and did not give up. Importantly, he had a dream just like Dr Martin Luther King Jr.

In conclusion, representation matters. Young pupils deserve a diverse education, inspiration and representation. Fundamentally, it is pivotal that they see leaders from diverse backgrounds to prepare them for the world of work. I believe that it would be beneficial to have more black and global majority leaders like Nadine Bernard leading conferences to elevate future generations and make a difference. Nadine has started a legacy. The next step is a follow-up conference.

Audit Your Curriculum for Gender and LGBTQ+ Inclusivity

Written by Katherine Fowler

Katherine Fowler is a specialist content editor at The Key, a provider of up-to-the-minute sector intelligence and resources that empower education leaders with the knowledge to act.

Committing to improving diversity across your school’s curriculum is a big task, but it’s also a really important one. You’ll know that lasting change isn’t created by talking about gender and sexuality in a few PSHE or RSE lessons, but by really taking time to embed inclusivity throughout your curriculum. So how can you do this?

- Ask questions of your current curriculum. In particular, look for weaknesses or gaps in each subject and consider how you can fill these with inclusive materials (such as books written by female authors, or LGBTQ+ STEM role models). Specialist audit tools are available to help you spot these gaps and make changes, such as The Key’s LGBTQ+ and gender curriculum audit tool.

- Always take a moment to think about intersectionality. While you’re focusing on your representation of women and LGBTQ+ in your curriculum, it can be easy to slip into defaulting to, for example, white, able-bodied examples. Try to balance your examples to include women and LGBTQ+ people of colour, and of different abilities and body types.

- Encourage staff to educate themselves. If your staff don’t understand the importance of doing this sort of curriculum review, you’re not going to achieve lasting change. Ideally, you’d want to spend time with all your staff, but, if time and resources are tight, at least make sure the staff who are going to take the lead on the audit are aware of current issues surrounding gender and sexuality. There’s a host of reading material, podcasts, documentaries and TV shows that cover these topics – signpost some to your staff, and make sure they are given an opportunity to discuss their thoughts and feelings (for example, in a dedicated staff meeting).

- Create a cross-curricular working group to take the lead. As already mentioned, committing to this curriculum review is a large task, and shouldn’t be put on the shoulders of one or two people. Get a group of staff together to work on this instead. As a minimum, you’d want to involve:

- The subject leader/co-ordinator for each subject

- PSHE/RSE leads, who will be most familiar with the content of this audit

- Any other members of staff who show interest in the work (these don’t have to be teachers – passion is what’s key!)

Even though different members of the group will be focused on different parts of your curriculum, the kinds of questions in an audit and their overall aims should be aligned, so encourage them to work together and support each other.

Useful documents to review include:

- Curriculum maps

- Short and long-term plans

- Individual lesson plans and resources

The working group should also take into account cross-curricular events/days, trips and assemblies.

Get the working group to meet regularly and review progress. This also lets the group share ideas and resources. Aim for a meeting at least once a term, but half-termly would be ideal.

- Involve the wider community. Consider running an INSET or CPD session for all staff to kick-off the curriculum review, to encourage interest and participation. All staff should feel able to feed in suggestions or ideas of what needs to improve via their subject leader.

Parents and pupils should also know that you’re carrying out this audit and be able to share their thoughts and ideas.

Your governors should know you’re doing this, too, especially any curriculum link governors. Give them the opportunity to get involved in the working group if they’re keen!

- Be prepared for this to take time. A full review could take up to a year, and will never truly be ‘finished’ – your working group should continue to meet, review and look for more ways to adapt and refine the curriculum. Encourage this by making sure the group has protected time, such as INSET days and staff meetings, to dedicate to the work. Consider adding the audit to your school improvement plan, so the work gets tracked and resources can be considered at the start.

- Go beyond your curriculum, too. If you want a truly inclusive environment, you’ll need to think about the ethos and culture that surrounds your curriculum. Consider whether you can improve inclusivity in the following areas:

- Staff hiring and training

- The school environment (e.g. displays, shared spaces such as the library)

- Policies (e.g. anti-bullying policy, behaviour policy and child protection policy)

- Meeting your requirements under the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED)

- The language used across your school (Stonewall’s primary curriculum contains useful glossaries for pupils and staff)

- Your school’s involvement and engagement with your wider community

How can we raise anti-racist leaders?

Written by Ayo Awotona

Ayo Awotona specializes in confidence building for girls in education. She does this through programs, workshops, and keynote speeches.

When it comes to speaking about race, white privilege, and colorism; things can often get a tad bit uncomfortable or even awkward, to say the least.

This is understandable. More often than not, these are difficult conversations for most people, and difficult conversations are often characterized by emotions such as fear, anger, frustration, conflict, and other strong dividing — not unifying — emotions. These emotions are often suppressed and can be released rather strongly.

Why is this?

It’s because emotions can run high on both sides, and there is room for the conversation to become quite heated on either or both sides.

This is just one perspective as to why uncomfortable conversations are hard.

So I hope that takes some pressure off of you depending on your curiosity as you first read the title to this blog post 🙂

So let’s dive into this simple (yet, rather complex) question.

How can we raise anti-racist leaders? That is, how can we empower our young people in the world today to make a change by first recognizing racism and challenging it in this seemingly never-ending cycle of systemic oppression?

Before I continue, I must add here that this question is not thrown out to one particular race. This is a question that’s being thrown to each and every one of us reading this (yes! Even me as a Black-British Nigerian woman), because the reality is… change starts with every single one of us. All races and denominations. Change looks different on each and every one of us – rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

To kick us off with answering this question, it’s important for us to acknowledge/be reminded that children are not colorblind. Children are very much aware of racial differences.

Permit me to simplify how young children learn about race to:

- what they see (both directly and indirectly),

- what they hear, and;

- what they are taught (both at home and in school).

This is really encouraging because it means we (as educators and leaders) play a big role in positively influencing the trajectory of their lives.

Now let’s talk about developing an anti-racism strategy for our young people.

There are different ways to make a change so I’ll give 3 examples of practical things that can be done to help raise anti-racist leaders.

Behavioural Change

As leaders, we ought to know and lead ourselves before we lead others. This means we essentially can’t give what we don’t have. Here are some tips for being intentional about our own growth:

- Listen to other perspectives and de-center yourself

- Boost the voices of the marginalized

- Educate yourself

- Acknowledge your own privilege and propensity for unconscious bias

- Challenge discrimination, even when you feel scared

- Keep the conversation going

Raising Awareness

Sometimes, one of the most powerful things we can offer young people is awareness. This is where we’re focusing their attention on a cause or issue in the world (in this case, related to race). The objective is to increase their understanding – but of course, we must be in a position where we are practicing this ourselves.

Action Planning

A great way to empower young people to take charge of their own learning is through projects – whether this is through achieving tangible or intangible objectives. Action planning activities are designed to support students to build the necessary skills for work and life, as active local and global citizens.

So what could this look like?

Running a workshop where students come up with a project idea to take action on!

During the workshop and overall project duration, it’s important that we support students with their ideas, but steer them in the direction of what is realistic. It is important not to stamp out their creativity, but equally important to ensure students have a clear understanding of how their action plan can be S.M.A.R.T. (Specific. Measurable. Attainable. Relevant. Time-bound)

Some suggested questions to guide your students are:

- What issues do you see happening in your local community that make you upset/angry/you would like to change?

- What issues do you know of happening in your global community? Have you read or seen anything in the news recently?

- If you could change one thing in your local/global community, what would it be?

I strongly believe that for us to move in the right direction of raising anti-racist leaders, change starts with both you and me.

My name is Ayo, Ayo Awotona.

Let’s keep the conversation ALIVE!

Building Leadership Presence through Awareness of Self

Written by Yamina Bibi

English Teacher and Assistant Headteacher

During the #WomenEd Global Unconference 2021, I spoke about how we can go about tackling our inner critic so that we can limit the influence of it on us as women.

I shared some specific strategies that have really helped me like labelling how I am feeling and seeking support from other women through coaching.

Despite presenting on this, I have really struggled this week to mute my unkind inner critic.

Having started as an AHT role in a new school this year, I have felt like a novice despite being a senior leader for a few years now. I guess in some ways I am because I am new to the system, rules and routines of the school. I know that it’s normal to feel this way but unfortunately this week I have been unable to soothe my inner critic, which tells me that I should be able to do this since I’ve done this job before. This negative self talk then creates a heaviness in my heart and mind and has even stopped me from sleeping well.

These are the unkind things that have played over and over again in my head:

‘You’ve been doing this for a while and you’re still not good.’

‘You can’t even teach properly so what makes you think you can lead?’

‘You were better as a classroom teacher instead of being SLT.’

Through coaching, I have been able to listen to this negative self talk and interrupt my tendency of letting it control me and all I do. I have learned to notice when I go from pressure to stress and acknowledge these thoughts and feelings. I have learned to notice when I am comparing myself to others and telling myself that I’m not good enough because they are better.

However, what I’ve really noticed is that when we’re on social media, it’s so easy to assume that everything and everyone else is doing better than us. It’s easy to believe that other teachers and leaders are superhuman experts who know all there is to know and can do everything and that, in comparison, we can’t do anything.

Let’s be honest. In schools, we are all working hard especially during these challenging times. We are all doing our best for our staff and students but no, we don’t know everything and it’s absolutely fine to say that.

As part of Resilient Leaders Elements™, we learn to share our strengths as well as our areas of development. I’ve been so afraid to do this in the past because I have feared that everyone would know what I knew about myself: I’m a fraud and failure. I now know that being open about my developmental needs with the people I trust and who support me does not make me a failure, it makes me an authentic leader.

Before RLE, I always thought I was an authentic leader but I realised that only allowing people to see my strengths and never sharing my struggles meant that others thought I was a superwoman. Maybe that’s what I wanted then but I definitely don’t want that anymore.

As leaders, we have a duty to model vulnerability and authenticity. True authentic leaders increase their leadership presence by modelling that we all have strengths and areas of development. In sharing this, hopefully others in our sphere of influence will do the same and then we can truly support them and their needs.

Alongside this, we must also pause, reflect and acknowledge our successes. Write it down, read it on paper and read it aloud to ourselves and others. What we are doing is so important and we cannot diminish that because our inner critic is telling us otherwise.

Let’s share all of who we are so that we can continue doing what we love without fear and that unkind inner critic holding us back.

Men, women and the rest of us: a brief guide to making university classrooms more accessible to trans and gender non-conforming students

Written by Kit Heyam and Onni Gust

Onni Gust: Associate Professor of History, University of Nottingham. Author of Unhomely Empire: Whiteness and Belonging, c.1760-1830.Kit Heyam: Lecturer in Medieval and Early Modern Studies at Queen Mary, University of London, freelance trans awareness trainer, and queer public history activist.

This is a guide for academic teachers who want to get the best out of their trans and gender non-conforming students, and to ensure that they can fully participate in the classroom and in their studies.

1. Avoid making assumptions

Don’t assume you know a student’s gender based on body-type, voice or even dress. If they do disclose their trans status, don’t assume that they have or will undergo any form of medical transition; ask them how you can support them. All you really need to know is how to address them.

2. Names and pronouns are all you need

Names and pronouns are all you really need to know from your students. For trans and gender non-conforming students, the name, sex or title on their student record may be wrong. Using a student’s ‘old’ name may force them to come out, which can be incredibly distressing as well as violating the Equality Act. To avoid this:

Names:

- Instead of calling out the register, ask students to either write or say their names.

- Be up-front with students and ask them to see you, or email you, after class if for any reason their name has changed.

- Online platforms often automatically display names from University records. Familiarise yourself with your university’s name-changing processes – and if there aren’t any, insist that they be put in place.

Pronouns:

- Even if you think it’s obvious, explain to students how you like to be addressed. This models the process for all students and makes it much easier for trans and gender non-conforming students to state their own pronouns. Regardless of whether you’re trans or not, it also sends a powerful signal, showing you’re aware you can’t tell someone’s gender just from looking at them.

- If you ask students to introduce themselves to the class, give them the opportunity, but not the obligation, to include their pronouns.

- Gender-neutral pronouns, which some students will use, include the singular they/them/their; ze/hir/hirs; fae/faer/faers. The list is growing: if you’re unsure, ask the student to model the usage for you, or research it online.

- If you get a student’s pronoun wrong, apologise, correct yourself and move on.

3. What if other students constantly misgender a student in your class?

If a trans or gender non-conforming student brings this to your attention, it may be worth taking that student aside and talking to them. If, as a transgender teacher, I suspect that this is active transphobia, I would probably ask a cisgender colleague to intervene.

4. How else can I make learning more inclusive?

Consider your syllabus. It may be necessary to teach material that uses outdated/pejorative language, or ideas, about gender and sexuality (and/or race, class and disability). Flag up the problems, explain to your students why these texts are necessary to engage with, but make it clear that you do not support these ideas and that you invite critique.

Think about how you’ll manage any resulting questions or disagreements. How can you help your students to create a trans-inclusive seminar environment without making them feel overwhelmed, alienated or defensive?

5. Pastoral care for trans and gender non-conforming students

Awareness of trans and gender non-conforming identities is moving at a fast, but very uneven, pace. While your students will hopefully have support at home and at university, that’s still not the case for the majority. In a recent UCAS report, 17% of trans university applicants reported having had a bad experience at school or college, and trans applicants were less likely than LGB applicants to have good expectations for university. The report recommends that universities and colleges introduce bespoke resources to support trans students.

Trans people remain disproportionately affected by mental health problems.If your trans and gender non-conforming students disclose mental health problems to you, treat them as you would any other student, butbear in mind the following:

- Not enough counselors or GPs are trans-aware; some have been known to do more harm than good.

- Specialist gender services have waiting lists of over two years from referral by a GP.

If a student comes out to you as trans part-way through a semester:

- Think about your reaction: this is a vulnerable moment for the student. If you don’t understand something, ask politely and calmly for clarification.

- Don’t make any assumptions: trans people differ in their identities and their choices about social and/or medical transition.

- Let the student take the lead: support them if they want to come out to their class, but don’t force it.

Further resources:

For you:

UCAS, Next steps: What is the experience of LGBT+ students in education?

Equality Challenge Unit, Trans staff and students in HE and colleges: improving experiences

For trans and gender-nonconforming students:

GIRES (Gender Identity Research & Education Society – including a directory of support groups)

Empowering Our Students - Let’s Start With Their Names

Written by Anu Roy

Anu is a TeachFirst leadership Alumni and digital trustee and teacher committee lead for charities in England and Scotland. She is currently a digital curriculum development manager and works in inclusive education projects incorporating tech.

I remember as a quiet and nervous NQT attending a meeting where myself and other English staff would chat about our incoming Year 7 cohort. As we worked our way through the Excel spreadsheet, a joke started forming where a member of staff referred to a student as ‘Chaka Khan’- alluding to the famous singer who goes by the same name. It felt harmless and I am sure the intention was not to cause embarrassment or mock names, but it felt wrong regardless. I would know. I am sure this happened when I moved from India to Wolverhampton to start Year 7 in a predominantly white school.

I remember all too clearly squirming at the back of a classroom when a teacher confidently made their way through ‘Beth, Laura, Jess, Zoe’ and then the dreaded moment came closer. The teacher paused, squinted at the list with a frown on their face.

‘Ama?

Amu?

Anaaa…’

Now the girls in the room were sniggering. They glanced back at me quickly and I did my best to force a small, to laugh it off even though I felt so humiliated inside. Especially because at that very moment the teacher who could not pronounce

‘Ah-New-Rad-ha’ gave up altogether and said, ‘it’s too much for me. Can we just call you Annie?’.

To have my name, my Bengali name given to me by my grandfather- a name which means ‘goddess of the gods’- reduced so casually to a westernized format that would be comfortable and convenient for my white teacher set the tone for my experience of education that year in Wolverhampton. It made me squirm whenever attendance was taken, it made me hesitant to raise my hand despite being confident about my subject knowledge and eventually-it made me reluctant about going to school. I wanted to feel invisible, to blend into the classroom walls because I was not British enough, I did not feel valuable.

So fast forward 11 years and now I am the teacher. I am supposed to have more knowledge, more acceptance and confidence. However, in that meeting when this student had their name turned into a joke, I felt the same pangs of feeling small, feeling embarrassed on their behalf.

So I spoke up, “it’s actually Shah-kir. Shakir Khan”. This was followed by some nodding, an acknowledgement of the changed atmosphere in the room and we moved on quickly to the next student.

BAME students experience incidents like this every day and this must change. Here are some simple ways for educators to ensure this is avoided:

- Ask them exactly how you would like their name to be pronounced

- If you can, ask them where their name comes from. Many ethnic-minority names have symbolic religious and cultural meanings.

- Do not hesitate to correct colleagues who mispronounce a name in front of you if you are aware of the correct version

Our names are the blueprint of our identity. Let us ensure we honour this for our students.

Alopecia Awareness

Written by Zoe Reynolds

Head of MIS & Compliance, The National College of Education.

Alopecia is an autoimmune disorder that causes your hair to come out, often in clumps the size and shape of a quarter. The amount of hair loss is different in everyone. When you have alopecia, cells in your immune system surround and attack your hair follicles (the part of your body that makes hair). This attack on a hair follicle causes the attached hair to fall out. The more hair follicles that your immune system attacks, the more hair loss you will have. Some people lose it only in a few spots. Others lose a lot. Sometimes, hair grows back but falls out again later. In others, hair grows back for good.

Alopecia Symptoms

The main and often the only symptom of alopecia is hair loss. You may notice:

- Small bald patches on your scalp or other parts of your body

- Patches may get larger and grow together into a bald spot

- Hair grows back in one spot and falls out in another

- You lose a lot of hair over a short time

- More hair loss in cold weather

- Fingernails and toenails become red, brittle, and pitted

The bald patches of skin are smooth, with no rash or redness. But you may feel a tingling, itching, or burning sensation on your skin right before the hair falls out.

Myth #1: There is only one type of alopecia

People tend to be under the assumption alopecia is just, well, hair loss. Interestingly enough, alopecia IS the medical term to describe any type of hair loss. However, there are actually several types of alopecia, each affecting different parts of the body and occuring for various reasons.

- Alopecia Areata Patchy – Causes small, round patches of hair to fall out. Hair loss is usually temporary but can occur continuously over time.

- Alopecia Areata Totalis – Causes total hair loss on the scalp. This type of hair loss is also temporary.

- Alopecia Areata Universalis – Loss of hair on the entire body. Depending on the person’s history, this condition may be temporary or permanent.

- Traction Alopecia – Caused by tight hairstyles and hair pulling. This form of alopecia can be temporary if caught early. If not, continued stress on the scalp can lead to scarring or damage to the hair follicle.

- Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia/CCCA – CCCA can cause permanent hair loss due to follicle scarring if not caught early. While this form of alopecia is considered more common in middle-aged African American women, anyone can be susceptible.

- Androgenetic Alopecia – Also known as male or female pattern baldness, this form of alopecia refers to a degeneration of the hairline and is usually permanent. Those who experience Androgenetic Alopecia are most commonly genetically predisposed.

- Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia – This type of alopecia most frequently affects post menopausal women. With this type, a band of hair loss normally appears on the front and sides of the forehead and typically worsens over time.

Myth #2: It’s Contagious

Alopecia areata is not contagious. A bacteria or virus does not cause it, so there is no method to “transport” it to other people, or even new areas of the body.

Myth #3 There is No Treatment

This one is a bit tricky. While many FDA approved medications are being used to treat alopecia, they were approved for other conditions. So, there is no specific treatment for alopecia, but there are still many possibilities that can help.

Myth #4: Hair Will Never Grow Back

Hair growth and fall out are different for everyone. It can regrow spontaneously with or without treatment, then fall out again. There is no way to tell. Some prefer a wig or other product versus medications due to this reason.

Myth #5: Alopecia is Genetic

Alopecia is a polygenic disease. It means that both parents must be a contributor to a specific number of genes for a child to develop it. Most parents will not pass it onto their children because of several factors, both environmental and genetic need to trigger it.

Frequently asked questions:

When out in public, naturally curiosity gets the cat and people tend to stare and ask questions, such as… What made you shave your head? Do you have cancer? Doesn’t your head get burnt?

Depending on the individual and how comfortable they are with their alopecia they will often engage back to help spread awareness and educate others. For me personally, if you want to ask me anything please do not feel like you would be offending me.

The Kate Clanchy Memoir: A Red Flag for DEI

Written by Chiaka Amadi

Chiaka has almost 40 years of experience as a teacher and EAL leader at school and local authority level. Her work as an independent consultant and trainer focuses on language acquisition, literacy development and multilingualism.

In August, I read a succession of tweets about attacks on three WoC writers, Chimene Suleyman, Monisha Rajesh and Sunny Singh which alerted me to the controversy around a book ‘What I Taught Kids and What They Taught Me’. https://minamaauthor.com/2021/08/15/a-controversy-i-recently-read/?like_comment=242

The WoC had challenged the racialised and stereotyped language used by its author, Kate Clanchy, to describe her students. Numerous passages were criticised by a range of commentators citing derogatory descriptions of neurodiverse students; of some students’ choice of clothing; of the very carrying of their bodies. The lively discussion of the book on #DiReadsClanchy was then illuminating in helping me to understand the range of concerns concerning the depictions of the students.

What astonished me the most, however, was how such content could have ever been published as the considered writings of a teacher. How did the editors at Picador, Ms Clanchy’s publishers, perceive her writing? How could those critiqued sections of the book not have rung alarm bells during the editing process?

Even if knowledge of the protected characteristics in the Equality Act 2010 didn’t alert editors to the need for sensitivity and respect in relation to Ms Clanchy’s students, a quick read of Part Two of The Teachers Standards should at least have made them ask if its “high standards of ethics and behaviour” were being fulfilled: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1007716/Teachers__Standards_2021_update.pdf

Did the editors really believe that the words in front of them truly treated pupils with “dignity” and were “rooted in mutual respect”?

It is the children in the book who flag up that there are different life realities, experiences and perceptions at work. Ms Clanchy acknowledges that they teach her “how white I am” and explains to the reader the way the children encode her “super-empowered” membership of the “world’s ruling class” into the word “English”. Did the editors really not feel the need to explore that dynamic both as it appeared on the page and as it evolved as a conceit throughout the book?

Or did Ms Clanchy avoid this particular lesson by diverting to the fact that she is Scottish? This artful manoeuvre leads to the uncritical acceptance by the editors and subsequently by many readers, of Ms Clanchy’s first person narrative. It centres the perspective of a white, middle-class, well educated, abled person as the default for our interpretation. It invites the reader to peer through that particular lens at the students, and as ‘we’ do so, ‘we’ lap up her observations about them and about social matters. ‘We’ are in danger of objectifying and diminishing any student described who does not fit into that normative default, even as Ms Clanchy thinks she is being positive. This is a red flag for DEI activism.

Picador have announced a re-write of the book to remove any “offensive passages”: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/aug/10/kate-clanchy-to-rewrite-memoir-after-criticism-of-racist-and-ableist-tropes. Various idioms come to mind, the most polite involving silk purses and sow’s ears. While Ms Clanchy claimed that listening to recent responses to her work had been “humbling”, her publishers by contrast seemed energised, recruiting “specialist readers” to assist with the re-working.

To express my concern at all this, I recently signed an open letter to the publishers: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1EWl1D-Duw2qiwAWUsRANfo8VcqzDMANJ/edit

Picador have now replied to the 350+ signatories of this letter and you can read and evaluate that response here:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1e0uNH-ivVWBhXav7VD5yl_1mt5CgyAkz/view?usp=sharing.

Please comment if you wish. The feedback is being collated for return to Picador.

I was also pleased to read an open letter from a group of Ms Clanchy’s former pupils: https://www.thebookseller.com/news/clanchy-students-say-they-did-not-experience-safeguarding-or-consent-issues-1278744. I felt able to infer from their articulate and cogent advocacy on behalf of their teacher that their school experiences had contributed to an understanding what it takes to feel part of a community; of the give and take, the to and fro that is part of learning and teaching. They feel safe and confident. Their personal relationship with their former teacher is intact and strong.

However, we cannot shrug our shoulders and say, ‘all’s well that ends well’. To date, no concrete assurances have been given regarding the future ethical standards we can expect from Picador in relation to non-fiction writing about children. The issue is not about the affection or regard that any individuals might hold for others, but the wider debate around representation, ethics, literature and publishing.

As teachers, safeguarding children sits at the heart of our role. All stakeholders in education must ensure that our work does not reinforce stereotypical and clichéd views of children. The whole episode serves as a timely reminder of the need for each of us, in our own contexts to reflect on exactly what our gaze encapsulates. We must consider how our conversations and interactions with, and about children, respect their individuality and humanity. Our words can become wider, more permanent representations of them. We must endeavour to do no harm.

Afro Hair: The Petting Microaggression

Written by Adeola Ogundele

Adeola Ogundele is Head of Year 9, Head of Media Studies and a Teacher of English who has completed her NPQSL. She is a passionate advocate for Equality and Diversity. She tweets as @ao1982_

As black women, we have a very close relationship with our hair. Our hair is more than just keratin, it’s a badge of pride and honour because of the history behind it. Let’s celebrate World Afro Day on 15th September with the global The Big Hair Assembly.

In the late 1700s to the 1800s, there was a law – the Tignon Laws. This law demanded that women of colour cover their hair with fabric cloth. This law was introduced to curtail the growing influence of the free black population and keep the social order of the time. It was believed that black women were exhibiting unacceptable behaviours, which included the hairstyles they wore. These hairstyles drew the attention of white men. Black women were, apparently, wearing their hair in such lovely ways; adding jewels and feathers to their high hairdos and walking around with such beauty and pride, that it was obscuring their status. This disrupted the social stability of white women. Therefore, the law was introduced to minimise a black woman’s beauty. In many societies, white women would cut off a black woman’s hair, as they felt that her hair ‘confused white men’.

Without the fancy hairstyles of black women, white women believed that black hair, in its natural state, was ugly. White was the epitome of beauty, the straight hair and the fair skin. So, the further a person was from fitting with that ideal, the more unattractive they were deemed to be.

Slavery was abolished in the 19th century. As black women were free, they felt pressure to fit in with the European ideals and therefore adapted their hairstyles.

‘Black people felt compelled to smoothen their hair and texture to fit in easier, and to move in society better and in camouflage almost,’ says exhibition producer Aaryn Lynch.

‘I’ve nicknamed the post-emancipation era ‘the great oppression’ because that’s when black people had to go through really intensive methods to smooth their hair. “Men and women would put their hair in a hot chemical mixture that would almost burn their scalp, so they could comb it back and make it look more European and silky.’ Chemically straightening hair was often called relaxing the hair, a problematic term. Or perming the hair, as it was permanently straightened – until the new growth came through and you’d have to apply more chemicals to the new growth.

During the civil rights movement, black people began wearing their Afros and it was seen as a political statement and a form of rebellion. Black people felt a sense of pride and as they protested against racial segregation and oppression, the eye-catching style took off – an assertion of black identity in contrast to previous trends inspired by mainstream white fashions. Unfortunately, that’s all the Afro was, a political statement and a form of rebellion. When in fact, an Afro is the natural state of a black person’s hair. However, because black women have adapted to the European beauty ideals for so long, the Afro and the Afro hairstyles are seen as against the ‘norm’.

It was only when I was in my early 30s that I knew what my natural hair texture was like. There is a range of natural hair types. My hair is probably a 4a with some parts that are 4b and it is also very thin. I have always known that it was thin but I never knew the texture of it. I never knew the texture because my mum relaxed/permed my hair when I was really young. While I was in school, most of the black girls also had relaxed/permed hair. It was believed to be ‘easier to manage’ and it also ‘looked nicer’ – because it was straight. Obviously, these were unconscious ideas that were ingrained within us as a result of white supremacy.

This Morning presenter, Eamonn Holmes, told Dr Zoe Williams that her hair reminded him ‘of an alpaca’. He continued with, ‘You just want to pet it.’ Dr Zoe Williams laughed along and jovially responded with, ‘Don’t touch my hair!’.Black women have been faced with several micro-aggressions regarding their hair and the way to navigate it and to avoid being referred to as angry, is to laugh along. However, Dr Zoe William’s reference to the very well-known phrase ‘don’t touch my hair’ is an indication that she didn’t receive Eamonn Holmes’ comment well.

According to a study conducted earlier this year, it was found that black people experience ‘racial trauma’ because of frequent afro hair discrimination. At least 93% of Black people with Afro hair in the UK have experienced microaggressions related to their hair, and 52% say discrimination against their hair has negatively affected their self-esteem or mental health. So, describing a Black woman’s hair as animal fur and saying that you would like to ‘pet’ it, contributes to this damaging trend of ‘othering’ by treating Afro hair as a fascination. It is also very offensive.

Many people may fail to understand why comments about black hair can be so damaging, considering hair being superficial. But Afro hair is, unfortunately, political. Black people are punished and excluded from certain spaces because of the way their hair grows naturally on their heads.

‘Hair is a sensitive topic for black and mixed-race women as a lot of us still struggle with how to manage it, along with a lack of diversity in products in mainstream stores – so it’s like twisting the knife.’ says Keisha East, natural hair blogger and influencer.

Keshia adds that black women already feel pressure to conform to European beauty standards, particularly in professional spaces. ‘It can be really damaging to our self-esteem,’ she adds. ‘Quite frankly, negative conversations around our hair can be exhausting, as we already face so many other challenges.’

There is a culture of it being okay to be ignorant towards black hair. However, why are so many ignorant towards our hair? It’s because we either straighten it, to fit in with social norms or wear extensions as a form of protection and/or to hide it away because we know that our hair is not seen as acceptable in a professional setting.

We often find that white people have a desire to touch our hair because it’s ‘different’ and they’re curious. However, this is a huge invasion of our privacy and, considering that black women are underrepresented in the media and the representation usually being where we fit the European beauty ideals, touching our hair and the fascination with our hair, is a symptom of unconscious bias informed by white supremacy. In the context of the history of black people’s bodies and looks being objectified, dehumanised and marginalised, the impulse for white people to touch black women’s hair sends the message that our bodies are there as objects to be touched and looked at.

I’ve never looked at a white person’s straight hair and been shocked by it or found it amazing. I’m also used to seeing it, as it’s what the media and society has told me is the ‘norm’ and therefore, beautiful. However, a black person’s hair isn’t seen the same way. The way a black person’s hair grows out of the head is seen as something of an amazement, a form of rebellion or unprofessional.

There has been the rebuttal, ‘My hair is curly and people always want to touch it, and I’m white.’ Right! That’s the point being made. People want to touch your curly hair because it’s seen as an anomaly. It’s not seen as ‘normal’ hair, hence people being fascinated by it. Also a white person’s curly hair is probably a 3b at most. Black people have curly hair (mainly type 4 hair), it’s our normal – but not the norm.

This needs to change.

The Importance of Empathy

Written by Rebecca Ferdinand

Marketing manager at Lyfta. She has a BSc in Psychology from Durham and has worked for a range of organisations including the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education.

Empathy is one of the fundamental values underpinning our work at Lyfta. In this blog we discuss the scientific evidence for empathy, and talk about how we can nurture it in ourselves and in the children we teach.

This blog first appeared on Lyfta.com. Lyfta is a partner organisation and supporter of DiverseEd.

At a time of continued global disruption and isolation, the importance of being able to have empathetic connections with others – to feel with them and care about their wellbeing – will be critical to ensuring that we build workplaces and societies that can thrive into the future. The children of today all have the potential to build a more peaceful and sustainable world, and empowering them with a strong sense of empathy will enable them to navigate this challenge with sensitivity and compassion.

“Empathy is a quality of character that can change the world.” Barack Obama

But what is empathy? Some confuse empathy (feeling with someone) with sympathy (feeling sorry for someone), but Dr Brené Brown does a good job of explaining this and highlighting Dr Theresa Wiseman’s four attributes of empathy: the ability to perceive others’ feelings, to not stand in judgement of those feelings, recognising or imagining the other person’s emotions, and communicating this effectively. When we connect empathetically, we have better relationships, we become better co-workers and managers, but more importantly, we become more compassionate people – and compassion is vital to a sustainable and humane future.

“Empathy has no script. There is no right way or wrong way to do it. It’s simply listening, holding space, withholding judgment, emotionally connecting, and communicating that incredibly healing message of ‘You’re not alone’.” Dr Brené Brown

Over the past two decades, the evidence that human beings are wired for empathy and social cooperation has grown considerably. Neuroscientists have identified areas of the brain that, if damaged or compromised, can affect our ability to identify and understand others’ feelings. Psychologists have shown that children as young as 18 months are capable of attributing mental states to other people. But empathy is not a fixed ability. Evidence suggests that we can continue to develop our capacity for understanding others throughout our lives, but busy lifestyles and our tendency to surround ourselves with people who look and think like us, mean that we are not often encouraged to take a moment to connect with others. So how can we actively become more understanding, and nurture this ability in the children we teach? Here are four ways we can develop empathy in ourselves and in others:

- Be curious. We increase our capacity for empathy when we interact with people outside of our usual social circle, and encounter lives and world-views very different from our own. You could actively seek out new perspectives by seeking out people on social media who you wouldn’t usually follow, or, if you’re brave enough, making the effort to start up meaningful conversations with any new people you encounter day-to-day.

Research has shown that reading fiction helps people to improve their ability to understand others. Try to seek out stories from as wide a range of perspectives as possible for both yourself and the children you teach. Of course, Lyfta can help you bring real human stories from around the world into your classroom.

- Challenge your prejudices. We all make assumptions about people, and often these are completely unconscious. These might be based around gender, age or racial stereotypes that prevent us from appreciating each person’s individuality. Our biases can seriously hinder our ability to become more empathetic, but acknowledging and challenging them is the first step toward becoming a more understanding person. You can learn more about your biases by taking an unconscious bias test, and tackle them by attending diversity, equity and inclusion workshops or discussions such as those run by the #DiverseEd community.

In the classroom, you could open up discussions on the nature of stereotyping and prejudice, and ensure that you expose your students to people, places and stories that defy widely held expectations. Lyfta gives you access to real immersive human stories from around the world, helping you to start conversations that might otherwise be difficult to initiate during lessons.

- Listen (and be vulnerable). Being an empathetic conversationalist means listening actively. Try to be completely present to the feelings that a person is communicating in their conversation with you. Whether it’s a quick chat with a colleague, or a catch-up with an old friend, do all you can to understand their emotional state and needs. You can model active listening with the children you teach by making sure you give them your full attention during one-on-one conversations, and by reflecting and repeating back what you think they may be feeling to make sure you fully understand.

It isn’t enough to just listen, however. Being vulnerable and revealing our honest thoughts and feelings to others is vital to the creation of strong empathic relationships with both adults and children.

- Take action. Volunteering can be a great way to experience other lives first hand, create real change, and model empathy to students you teach. You can also encourage your students to join (or set up) clubs at school, such as environmental or equalities clubs, or to take action in response to local issues such as going on a litter pick, or organising donations to a food bank in your area.

“Empathy has always been important. Through empathy we understand and support others; it helps us build trusted relationships and our own peace of mind. Building on the strong foundations developed by its founders, Lyfta, and the approach that it nurtures, helps teachers and students raise their awareness of what is going on around us, of other people’s lives and of the wider world. Such awareness is probably more important now than ever before – at school, at work, and in life. I am glad to have experienced and grateful for Lyfta’s contribution to raising awareness, thinking of others, and developing skills appropriate to learning development; to strengthening of empathy; and to building the capability of all students.” Gavin Dykes, Director of the Education World Forum

Nurturing empathy is one of Lyfta’s fundamental aims. We believe that empathy is the first, and possibly most important, step to building a more compassionate, sustainable and equitable world. Our real immersive human stories provide a powerful way to foster empathetic understanding by giving students access to a wide and diverse range of global perspectives, challenging their misconceptions, and motivating action.

Join a free webinar to find out more about using Lyfta’s impactful stories in the classroom, and access a free trial of the platform.