Seeing the Unseen

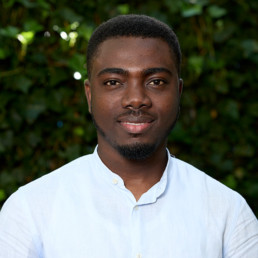

Written by Tyrone Sinclair

Tyrone is deputy headteacher of Addey & Stanhope School in London. He was a contributor to the BBC Teach resource, Supporting care-experienced children.

A significant majority of educators are drawn to the profession because they aspire to be catalysts for change. However, they are often taken aback by the limitations they encounter as they grapple with the multifaceted aspects of the profession. Change through support is a very delicate skill, one often not covered thoroughly whilst training, but it necessitates intentional leadership at an institutional level. Nonetheless, educators possess a unique liberty in that we are all leaders, regardless of our level of authority. We all possess the capacity to foster safety and facilitate opportunities for change within our respective spheres of influence, whether it be in our classrooms, through the curriculum, parental engagement, meetings, trips, and so forth – the possibilities are endless.

We are currently living in one of the most inclusive eras in human history. Whilst this allows for celebration, it also compels us to delve deeper and consider who is being included. Whose voices are being marginalised? Whose experiences are being disregarded? Who is seen and who is unseen? Ultimately, how is equity being applied in these circumstances?

The fight for inclusivity is a pursuit of social justice that extends far beyond the confines of the classroom. Its effects can be recognised and rewarded on a global scale. Although we may be making progress towards inclusive equity, it is important to acknowledge that not all spaces prioritise safety or consideration for all individuals. Education, therefore, is an embodiment of social justice as it endeavours to address the various inequalities that exist within society by creating opportunities and explicitly striving to provide equal opportunities for all.

This raises the question – what can I, as an educator, do? Amidst the external pressures, deadlines, targets, and ever-expanding job description, how can I make a meaningful change?

I believe the answer lies not in what can be done, but rather in how it can be done. I have been challenging educators to reconsider the spaces they create for safety. I urge them to contemplate the most vulnerable student who may ever enter their classrooms. Consider all the safeguarding concerns, whether they are rooted in familial or contextual factors. Reflect on the experiences these students have endured not only throughout their short lives, but even on that very morning. Contemplate the sacrifices and who they have to leave at the door just so they can walk into your space and conform.

Care-experienced young people are often among the most vulnerable individuals we encounter. The range of experiences they may have endured is vast, but more often than not, these experiences are far from ideal. Imagine the worst possible scenario. Consider the impact this must have on their worldview and how this trauma manifests itself in their thoughts, pathology, behaviours, and even their physical wellbeing. Now, take into account the intersectionalities that these young people may identify with. How much more challenging would it be for those from marginalised groups? How would you connect with such a young person? How would you welcome them into your space? What measures would you put in place to support, encourage, reassure, and protect them? How would you guide them if things went awry? Undoubtedly, your approach would be thoughtful, compassionate, and considerate. We know that for every vulnerable young person we are aware of and deem worthy of intervention, there are countless others who remain unknown and unsupported. Moreover, the strain on resources and support services makes it even more arduous for marginalised groups to access the help they need. Thus, your approach and support as an educator are pivotal to the safety and wellbeing of these young people, as your intervention may be the only kind they receive. Consequently, every interaction becomes an opportunity for intervention.

The experience of marginalised groups is to be unseen. This is often unintentional, but it is undeniably systemic and institutionalised. As educators, we are on the frontlines, and it is our duty to intentionally see what the world chooses to ignore. We must consciously consider worldviews and experiences that may differ fundamentally from our own. We must be intentional about change.

What can care-experienced young people teach us?

Acknowledging the unseen requires us to not only consider young people who have experienced care, but also challenges us to broaden our considerations even before they enter the system. Many care-experienced young people were once students in someone’s classroom, often unseen and unnoticed. However, we have the privilege of seeing the unseen and deliberately choosing to create safety for them within the spaces we control and have influence over.

For more information about the BBC Teach resource, Supporting care-experienced children, please visit https://tinyurl.com/ywykzd5h

Make Yourself Heard

Written by Bennie Kara

Co-Founder of Diverse Educators

Public speaking is a fact of life in the teaching profession. We speak to students all the time in classrooms, but every so often, we are called to deliver assemblies, or to deliver training to staff, or to speak to governors. Some of us are supremely confident in talking in front of students, but shudder at the thought of talking to a group of adults. If you’ve ever felt a sense of dread when you are asked to stand up and deliver spoken content outside of the classroom, you’re not alone. According to the British Council, 75% of us suffer from anxiety about talking in front of a crowd.

Speaking in front of the crowd may tap into a range of fears. We might fear being nervous and how that might affect our assignment. We might fear judgement, or fear that we won’t get everything across that we want to say. We might fear that people won’t listen. We might fear forgetting what we are saying in the moment, stumbling, freezing, feeling embarrassed. These are valid fears and affect most of us.

Whose voices are valued in the public space? Some people are less confident in their speaking abilities because their voices have been silenced. In the UK, global majority teachers work in a predominantly white British teaching workforce; we know the statistics on the ethnic make-up of leadership teams in education. Global majority teachers may suffer from the voicelessness that is part and parcel of existing in marginalised groups. This isn’t just true in terms of race and ethnicity; it is also true for sexuality, gender, disability, and neurodiversity.

Voicelessness erodes confidence. So it is hugely important that we learn how to find a voice in the public space and to feel like we belong there.

Finding your message

Regardless of the occasion, it is important to define the message. Speaking in a staff meeting, delivering a talk to parents – what is it that we want to get across? Not just in terms of the information, but also about you. How are you defining your leadership in the moment through what you say and how you say it?

The message might be small, or it might be momentous. In either case, we need to find ways to define a sense of who we are as engaging speakers and to ensure that we can convey our message effectively. This takes thought, planning, and crucially, constructive practice.

The best public speakers have elements in common. One of the most powerful tools in public speaking is your ability to tell a story. Storytelling is vital in public speaking, in the appropriate contexts. An assembly without a story, a keynote without anecdote can feel dry and impersonal. The most skilled public speakers I have encountered know how to weave a story into the talk with a deftness and ease that seems intuitive.

But storytelling is not intuitive for all. Some people are completely comfortable in selecting anecdotes, examples, stories, tiny useful narratives for the public engagement. Others have to think more carefully, but that careful process can lead to brilliant, engaging public speaking.

The Diverse Educators ‘Make Yourself Heard’ Course

Designing this course, for us, means that we can support you in developing the right mindset for public speaking and provide you with practical strategies to make yourself heard. It aims to develop a voice with you in small groups so that you have the chance to listen, learn, practise and hear feedback.

If you would like support in developing your voice, join us on the ‘Making Yourself Heard’ course using the details below:

Monday 15th January and Monday 11th March 4-5pm

Part 1 – Monday 15th January 2024 4.00-5.00pm

The first session is an intensive look at how you can plan, develop and deliver talk in public so that you can create impactful messages.

Part 2 – Monday 11th March 2024 4.00-5.00pm

This second session aims to support you in considering how to speak impactfully in public. It will cover planning, rehearsal and delivery style in a safe, supportive space with fellow educators.

Nb/ Both sessions will be held on zoom, they will be recorded so purchasing the recording is also an option if you are unable to make either of the dates.

Black History Month: Dismantling inequalities in education for better outcomes

Written by Henry Derben

Henry Derben is the Media, PR, and Policy Manager at Action Tutoring - an education charity that supports disadvantaged young people in primary and secondary to achieve academically and to enable them to progress in education, employment, or training by partnering high-quality volunteer tutors with pupils to increase their subject knowledge, confidence and study skills.

Before the pandemic disrupted education, students from Black ethnic backgrounds had the lowest pass rate among all major ethnic groups at the GCSE level. However, the 2022-23 GCSEs marked a notable shift from the pre-pandemic period, with Black students on average achieving similar English and maths pass rates comparable to students of other ethnic groups.

Black History Month is celebrated in October each year in the UK to recognise the historic achievements and contributions of the Black community. It is also a prime moment to reflect on the state of education and how it can be reshaped to create a more equitable and inclusive future.

As part of activities to mark Black History Month at Action Tutoring, we had an insightful conversation on how to ensure better outcomes and a more enabling environment for Black pupils in schools with Hannah Wilson, a co-founder of Diverse Educators, a coach, development consultant and trainer of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion practice. Hannah’s former roles in education include head of secondary teacher training, executive headteacher, and vice-chair of a trust board.

Below are some highlights of the conversation.

Re-examining Black history in the UK curriculum

Black History Month in the UK often focuses on the celebrated figures and events in mostly Black American history, such as the civil rights movement and famous Black personalities. However, Hannah highlights an important criticism – the lack of focus on UK Black identities.

“We want to move to the point where Black culture and identity are integrated throughout the curriculum,” Hannah explains, advocating for a more inclusive and comprehensive approach. The celebration of Black identity is that it’s often a lot of Black men being spoken about and not Black women, queer people, and disabled people. Thinking about that intersectionality and looking at the complexity and the hybridity of those different parts of identity often gets overlooked as well.”

A new Pupil Experience and Wellbeing survey by Edurio shows that pupils of Any Other Ethnic Group (48%) are 21% more likely to rarely or never feel that the curriculum reflects people like them than White British/Irish Students (27%). Additionally, Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups (16%) and Black/African/Caribbean/Black British students (18%) are the least likely to feel that the curriculum reflects them very or quite often.

Unpacking performance gaps

Data has shown that while a high percentage of Black students pursue higher education, they often struggle to obtain high grades, enter prestigious universities, secure highly skilled jobs, and experience career satisfaction. The journey to understanding the root causes of these educational disparities is a complex one.

Hannah recommended the need to rethink career education and the lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion strategies that often work in isolation.

“I don’t think all schools are carefully curating the visible role models they present. The adage about if you can’t see it can’t be it, and the awareness around the navigation into those different career pathways. I think that is saying that schools could do better. There’s a bridge there to be built around the pathways we are presenting as opportunities on the horizon for young people as well. Representation within the workforce is another key aspect. We need to address the lack of Black representation in leadership positions, not only in schools but also in higher education.”

The early years and disadvantage

Disadvantage often begins at an early age. Children from low-income backgrounds, including Black children, start school at a disadvantage. Hannah pointed out that the key to dismantling this cycle lies in reimagining the curriculum, the approach to teaching, and in valuing cultural consciousness.

“It’s important to start with the curriculum. The curriculum in the early years should be diverse and inclusive. The thought leaders within that provision or within that key stage are often quite white. That’s often the disconnect at a systemic level when it comes to policymaking around provision for the early years. Who is designing the policy for the early years? Who’s designing the curriculum for the early years? Are we being intentional about representation in the early years?”

“However, we need to move beyond simply adding diversity as a “bolt-on.” Their representation should be integral to the curriculum, not an afterthought. As young as our children join the education system, what can we do differently from the get-go to think about identity representation.”

Breaking the concrete ceiling

While tutoring is a viable method to help bridge the gap for underperforming students, Hannah stressed the need to change the system fundamentally. Rather than continually implementing interventions when problems arise, it’s best to revisit the structure of the school day, the diversity of teaching staff, and the core content of the curriculum.

“It has to start with the curriculum, surely tutoring and mentoring all of those interventions like mediation support mechanisms are so powerful, we know that make up the difference. But what are we actually doing to challenge the root cause? We have to stop softball. We’re often throwing money at the problem, but not actually fixing the problems or doing things differently. We need a big disruption and conscious commitment to change, but it needs to be collective.”

“We need to address the concrete ceiling that often prevents Black pupils from accessing leadership opportunities. Career guidance, sponsorship, and mentoring should be part of the solution to break these patterns. Collective action is essential to create lasting change.”

The power of engaged parents

Change should also start at home. Parents and guardians play a crucial role in a child’s education, particularly in the early years. Hannah suggests a shift in the dynamic between schools and parents.

“Thinking about how we work with parents and create a true partnership and collaboration. That to me, is what some schools perhaps need to revisit – their kind of plans, commitment, or the ways they work with different stakeholders. Engaging parents more closely is definitely a way of helping them get involved in schools so they’re part of that change cycle.”

The call to action for allies

In conclusion, Hannah’s powerful call to action focuses on allyship, encouraging non-Black people to actively support and contribute to the ongoing struggle for equity and inclusion in education.

I think for people who identify as being white, the reflection and awareness of your own experience with schooling, where your identity is constantly being affirmed and validated because you saw yourselves in the classroom, in the teachers, in the leaders, in the governors, and in the curriculum, that’s often taken for granted. It’s time for us to step back, see those gaps, and to appreciate how that affirms us, but how that could actually really erode someone’s sense of self when they don’t see themselves in all of those different spaces.”

There should be a conscious intention that educators make about what they teach, who they teach, and how they teach it, to really think about representation and the positive impact it has on young people. And being very mindful that we don’t then just perpetuate certain stereotypes and not doing pockets of representation and pockets of validation.”

Hannah’s insights underscore the urgency of addressing the disparities in our education system. As Black History Month wraps up, let’s heed the call to action and take collective steps toward a more inclusive and empowering education system that taps and nurtures the potential of all young Black students.

The Differences Between Equality and Equity

Written by Governors for Schools

Governors for School finds, places, and supports skilled volunteers as governors and trustees on school and academy boards. They support schools across England and Wales to run effectively by finding high calibre governors to bring their skills and expertise to the table – and improve education for children.

One of the reasons many governors volunteer their time to local school boards is to help make the educational landscape a fairer and more inclusive place. However, for all pupils to thrive, governors must appreciate the diverse and complex ways in which some members of the school community face a disproportionate number of educational obstacles compared to their peers. Such groups of pupils can include, but are not limited to:

- Pupils from less advantaged households.

- Students who have English as a second language.

- Pupils who have a disability as outlined by the Equality Act 2010.

- Members of the LGBTQ+ community.

- People from ethnic minority backgrounds.

- And much more.

Since launching our Inclusive Governance campaign, we’ve noted that one of the best ways governors can do their bit to make schools more inclusive is to make a conscious effort to discuss equality and equity in board meetings. But what do these terms mean?

Put simply, equality means treating everyone the same way, irrespective of factors such as status or identity. Equity, on the other hand, means treating people differently in certain circumstances for equality of opportunity to be possible.

Creating equity is important within society as it puts students on a more level playing field, leads to better social and economic outcomes across wider society, allows students to feel more engaged and looked after, and leaves staff feeling more confident that they’re succeeding in their role.

The following illustration from the Interaction Institute for Social Change demonstrates that while equality means giving everyone access to the same resources, some people may not be able to utilise these resources due to factors outside of their control. As such, governing boards must put measures in place to ensure their actions are both equal and equitable, ensuring every pupil has the same experience.

When it comes to speaking about providing equity within schools, it’s important that governing boards are…

- Advocating for equality and equity within the wider vision and strategic direction of a school.

Consider whether the school’s vision and strategic direction is relevant and beneficial to all pupils. Governors could, for example, ask questions about targeted measures the school is taking to raise attainment among less advantaged pupils or those with special educational needs and disability (SEND), as well as how they will measure success in this area. Beyond academic attainment, governors may ask questions about whether the school is living up to its stated values, such as community-mindedness, compassion, or friendship. For example, does the school provide reintegration support for vulnerable pupils who may have spent time outside of school? Is this support appropriate and tailored to their different and potentially complex needs?

- Having discussions with students, caregivers, staff, and other stakeholders to understand how policies and actions being taken by the school are likely to affect them.

Having meaningful discussions across the school community can be a great way to catch underlying flaws in current plans. For example, ensuring lighting and paint colours on walls take into consideration visually impaired children. Other issues could include talking to people within the transgender community about changes to policies surrounding changing their names on registers.

- Looking closely at budgets and determining whether the school’s financial decisions benefit pupils in an equitable way.

As a board, listening to every governor’s perspective about the allocation of resources is a great way to ascertain whether funds are appropriately spent. For example, a governor with a background in SEND issues may have a very different perspective from a governor with experience of an alternative provision education. As this campaign highlights, attracting governors from a wide range of backgrounds onto school boards is one of the best ways to ensure pupils from across the community are well-represented.

Catch up with the rest of our Inclusive Governance campaign

For more support on pushing for inclusive practices within your governing landscape, you can have a look at our campaign webpage. You can also follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, and/or Facebook for updates on the campaign.

Equality Act: The 10th protected characteristic?

Written by Matt Bromley

Matt Bromley is an education journalist, author, and advisor with twenty five years’ experience in teaching and leadership including as a secondary school headteacher and academy principal, further education college vice principal, and multi-academy trust director. Matt is a public speaker, trainer, initial teacher training lecturer, and school improvement advisor. He remains a practising teacher, currently working in secondary, FE and HE settings. Matt writes for various magazines, is the author of numerous best-selling books on education, and co-hosts an award-winning podcast.

This is an abridged version of an article that first appeared on the SecEd website on 13 November 2023. To read the full version, click here.

The Equality Act 2010 makes it unlawful for schools to discriminate against, harass or victimise a pupil or potential pupil in relation to admissions, in the way they provide education or access to any benefit, facility or service because of their:

- Sex

- Race

- Disability

- Religion or belief

- Sexual orientation

- Gender reassignment

- Pregnancy or maternity

These seven identifiers are called “protected characteristics”. There are nine in total, with “age” and “marriage and civil partnership” completing the list.

I don’t think the law goes far enough. I think there should be a 10th protected characteristic: social class. After all, class plays an important role in education and in later life…

Classism in education leads to underachievement and under-representation. Working-class students are among the lowest performers in our schools. If you’re a high-ability student from a low social class, you won’t do as well in school and in later life as a low-ability student from a high social class. It is social class and wealth – not ability – that define a pupil’s educational outcomes and their life chances.

Working-class people are also less likely to have a degree, work in professional employment, or be an academic compared to those from more elite backgrounds.

There are three problems with classism in schools:

- Curriculum design

The stated aim of the national curriculum is to ensure that all students in England encounter the same content and material to provide “an introduction to the essential knowledge that they need to be educated citizens”. There are two problems…

First, curriculum coverage – one size doesn’t fit all. Providing all students with the same curriculum further disadvantages those who are already disadvantaged.

We must deliver the same ambitious curriculum to every pupil. But we should offer more, not less – but, crucially, not the same – to working-class students. This may mean additional opportunities for those whose starting points are lower or for whom opportunities are more limited.

Second, curriculum content – definitions of core knowledge are classist. Selection of knowledge is made by those of a higher social standing rather than by a representative group of people from across the social strata.

Cultural capital is described as “the best that has been thought and said”, but who decides what constitutes the best? Ultimately, every school’s curriculum should celebrate working-class culture alongside culture from the dominant classes.

Also, we know that working-class students tend to be denied the experiences their middle-class peers are afforded, such as books at home, visiting museums and galleries, taking part in educational trips, foreign holidays and so on.

- Curriculum assessment

Our current assessment system could be regarded as classist. Let’s consider three elements:

- Home advantage: Those who don’t have a home life that is conducive to independent study are placed at a disadvantage, which is compounded for those who don’t have parents with the capacity to support them – whether in terms of time, ability, or buying resources.

- Content of exams: Exams tend to have a middle-class bias, such as requiring students to have personal experience of foreign travel or theatre visits.

- Exam outcomes: The assessment system is designed to fail a third of students every year – and it is the working classes who the suffer most. This is because the spread of GCSE grades is pegged to what cohorts of similar ability achieved in the past. Young people who fall below this bar pay a high price in terms of reduced prospects.

- The hidden curriculum

All schools have a hidden curriculum. It exists in a school’s rules and routines; in its behaviour policies, rewards, and sanctions; in its physical, social, and learning environments; and in the way all the adults who work in the school interact with each other and with the students. How sure can we be that our hidden curriculum does not discriminate against our working-class students?

Class a protected characteristic

If social class became the 10th protected characteristic, then schools would be required to:

- Remove or minimise disadvantages suffered by working-class pupils.

- Take steps to meet the particular needs of working-class pupils.

- Encourage working-class pupils to participate fully in a full range of school societies.

You can find out more about supporting working-class pupils in The Working Classroom, which has been written by Matt Bromley and Andy Griffith and is published by Crown House. For information and to access free resources, visit www.theworkingclassroom.co.uk

Attainment, Wellbeing and Recruitment

Written by Miriam Hussain

Miriam Hussain is a Director and Teacher of English within a Trust in the West Midlands. She has held a range of roles within education such as: Assistant Headteacher and Chair of Governors. She is also a Curriculum Associate and Ambassador for Teach First. Miriam is a Regional Lead for Litdrive, a charity and Subject Association for English teachers. She is also studying a Masters at the University of Oxford. Her twitter is @MiriamHussain_

The recent report from Sutton Trust (linked below) on the 19th of October 2023 stated that the attainment gap between disadvantage pupils and their peers had widened. This was massively concerning not only to me but a number of other school leaders across the country. The gap is now at its highest level since 2011, removing any progress made in the last decade. A gut-wrenching statistic. There are a lot of reasons for this, you only need to log on to Twitter (X) and see the quote tweets and replies to see people responding and citing the following: the government, economic and political inequality, social care and poverty. When I read the report however the first thing that cropped up into mind was recruitment. Having spent my career in working in schools in severe low socioeconomic deprivation but also disadvantage it made me think about the immense challenges for our young people today. The long list of barriers to social mobility for thousands of students alongside how would the best teachers be attracted to schools in these pressure cooker environments.

The Guardian in 2023 stated that almost a third of teachers who qualified in the last decade have since left the profession. This coupled with the growing attainment gap is a disaster. The article (linked below) went on to state that 13% of teachers in England that qualified in 2019 then resigned within two years resulting in 3000 teachers leaving the profession. They cited being overworked, stressed and not feeling value as the reasons. Ultimately, why work in education if you can get the same amount of money elsewhere or more, for less stress and work. How can we make teaching more attractive so that future talent doesn’t leave or quit. Ultimately, it will be these teachers who close the attainment gap so what do leaders within schools need to do to provide the conditions for teachers to stay;

- A wellbeing policy. Kat Howard in her blog (linked below) on Workload Perception states that wellbeing policies should be an explicit obligation to recognise the importance of taking care of staff. It is not a pizza party or copious amounts of high sugar foods on an evening where staff are expected to work late but instead a series of initiatives which support staff and elevate pressures throughout the year such as; giving time back to staff in the form of PPA at home, Golden tickets for staff where they can have a day for themselves via a raffle or specific initiatives through the year eg parents evenings, inviting people into meetings that only need to be there rather than everyone, having an email embargo of when emails can and can’t be sent. These are all important and need to be considered. Alongside, this its also having transparent conversations to support members of staff with flexible working with an ever-changing work force in addition to growing childcare commitments. These different viewpoints of work are critical. What I really enjoyed about Kat’s blog is that first and foremost having a wellbeing policy is ensuring that wellbeing is a reoccurring agenda item rather than a tick box activity. It forces the dialogue and critical conversations to change the face of education. It is providing policy led support for all stakeholders in education.

- Improve retention of staff via CPD. Leaders of schools need to be intentional with the CPD offer within their school or trust. How is the Professional Development meeting staff needs but more importantly developing them? What NPQs are staff being offered alongside leadership pathways within the trust or school? What does the next set of Middle or Senior Leadership look and feel like? Ultimately what is the offer you are giving to have the very best teachers working with your schools and trust to address the attainment gap?

- Schools have to offer a safe environment with a clear behaviour policy. If we want high calibre staff to teach in deprived areas leaders need to ensure that their staff are safe, SLT are visible and clear routines are being implemented. It is critical to ensure no learning time is lost as well as providing the right conditions within classrooms to address educational disadvantage. From my own experience an effective behaviour policy is the bedrock of any school. Students within these communities need consistent practices more than anything else. Clear procedures, habits and processes supports staff moral massively. The behaviour policy needs to be established and revisited daily.

- A good example of getting it right with a plethora of examples and research is of course Joe Kirby’s blog (linked below); Hornets, Slugs, Bees and Butterflies: not to do lists and the workload relief revolution. Critically it asks and answers how school leaders can support teachers and staff within education. There are many layers within the blog that I could delve into but what stood out to me was the Hornet section – High Effort, Low – impact initiatives within schools. Several Trusts implement these strategies on a daily basis, Pupil Progress meetings, Pointless Paperwork, Seating plans with data. They take a lot of time and within those high-pressure environments very little is done with that information afterwards it’s merely meeting a deadline. In the reality of school life, they are ineffective and unproductive. We then have slugs, copying out learning objectives, flight paths and big ideas with no detail. Instead, school cultures should be focused on the high impact strategies some of them described in the Kirby’s blog as; quizzes, booklets and sharing resources. Just because something has always been done does not mean that is how it always needs to me. With the recruitment crisis we are in we need to be thinking how we make schools flourishing institutions with systems that allow staff to do so.

I do believe these are within our control as leaders we need to be able to provide the right conditions and systems for our teachers, staff and individuals. Kat ends her blog with stating that in order to ‘improve conditions for all staff if time is taken’. Time being used to listen to what each stakeholder has to say and then making the necessary changes to have a positive and purposeful impact. Conversations should be seen as the framework that drives not only attainment, wellbeing and recruitment forward but all facets of school procedures. As Joe Kirby put it, less time on the Slugs and Hornets and more time on the Butterflies. Let’s stop wasting time in education.

References

Sutton Trust comment on Key Stage 4 performance data – Sutton Trust

Section 28: 20 Years On

Written by Hannah Wilson

Founder of Diverse Educators

Yesterday marked 20 years since Section 28 was repealed whilst also celebrating Trans Awareness Week. There is a brilliant thread on X here breaking down the key information all educators should know about this piece of problematic legislation which weaponised an identity group.

20 years ago, I had joined the teaching profession as a NQT at a boys’ school in Kent.

Homophobia was an issue.

I cannot remember having any training on my PGCE or in my NQT year about prejudice-based behaviour.

I cannot remember Section 28 being mentioned in either training programmes either.

After a year, I moved to London for a Head of Year role at a boys’ school in Surrey.

Homophobia was an issue.

But I felt more empowered to tackle it and I delivered the ‘Some People Are Gay – Get Over It! assemblies from Stonewall.

After three years, I then moved to a co-ed school in Mitcham.

Homophobia was an issue.

But we had strong whole school behaviour systems and consistent accountability so we tried to keep on top of it.

I also leveraged my pastoral and my curriculum leadership responsibilities to educate and to challenge the attitudes of our students.

After six years, I moved to a co-ed school in Morden as a Senior Leader (still in the same trust).

Homophobia was an issue.

But we had zero tolerance to discrimination and robust behaviour systems in place so we chipped away at it.

Three years later I relocated to Oxfordshire to be a Headteacher of a secondary school and Executive Headteacher of a primary school.

Homophobia was an issue.

But as a Headteacher with a committed SLT and visible role models, we hit it head on.

One of my favourite assembly moments in my twenty years in education was Bennie’s coming out assembly at our school. The courage and vulnerability she embodied as she shared the personal impact of the harmful attitudes, language and behaviour humanised the problem. We braced ourselves for the fallout, for the criticisms, but she was instead enveloped with love and respect by our community instead.

20 years on… six schools later…

Thousands of students… thousands of staff… thousands of parents and carers…

Homophobia was an issue – in every context, in every community, to a lesser or greater extent we have had to tackle prejudice and discrimination directed explicitly at the LGBTQ+ community.

Since leaving headship I have run a PGCE, consulted for national organisations, trained staff in schools, colleges and trusts (in the UK and internationally), coached senior leaders.

I am not a LGBTQ+ trainer – we have experts with lived experience who train on that. I speak about DEI strategy, inclusive cultures, inclusive language, inclusive behaviours and belonging. Yet, in every training session the experience of the LGBQT+ community comes up. It comes up especially with educators who started their careers in schools pre-2003 who talk about the shadow it has cast over them. It comes up with those starting their careers in schools asking when at interview you can ask if it is okay to be out.

Section 28 may have been repealed, we may be 20 years on, but have we really made any progress when it comes to tackling homophobia in our schools, in our communities and in our society?

Homophobia was and still is an issue.

As a cisgender, heterosexual woman homophobia has not personally impacted me. I have never had to hide my sexuality. I have been able to talk openly about who I am in a relationship with. I have not had to navigate assumptions, bias nor prejudice when it comes to who I date, who I love and who I commit to. This is a privilege I am aware of, but that I have also taken for granted.

A ‘big gay assembly’ may have been one of my professional highlights, but one of my personal low points was going on a night out to a gay club in Brighton in my early thirties, and my gay male friend being beaten up in the toilets in a supposed safe space by a homophobic straight man.

This is the reality for a lot of people I care about. Family, friends and colleagues who do not feel safe in our society. Members of my network who often do not feel safe in our schools.

It is our duty to ensure that our schools, our system and our society are safe for people to just be.

To be themselves… to be accepted… to be out at work (should they wish to be)… to be in love… to be able to talk about their relationships and their families…

It is our duty to ensure that we see progress in the next 20 years – as we are seeing a scary global regression of LGBTQ+ rights.

It is our duty to counter the current rhetoric – especially when it comes from our politicians who are weaponizing the LGBQT+ community.

It is our duty to challenge the haters and the trolls – if we as educators do not tackle it, then who else will?

Our gay students, staff, parents and carers need us to be allies. They need us to stand up, to speak out and to say this is not okay, this is enough.

Some signposting for organisations and resources to support you and your school:

Partnerships:

- Schools Out UK – they run LGBT History month and we collaborate on activities.

- Educate and Celebrate – they ran our LGBTQ+ training and school award for us.

- LGBTed – we hosted their launch at our very first #DiverseEd event.

- No Outsiders – we collaborate with them and celebrate their work.

- Pride and Progress – we partner with them and support their work.

- Just Like Us – we collaborate with them and amplify their Inclusion Week.

- Diversity Role Models – we collaborate with them and amplify their great resources.

- There are lots of other brilliant organisations and individuals working this space listed in our DEI Directory here.

Communities:

- ASCL – LGBTQ+ Leaders Network

- NAHT – LGBTQ+ Network

- NEU – LGBTQ+ Inclusion

- Pride and Progress – have an active P&P group in the #DiverseEd Mighty Network.

Books:

- Paul Baker – Outrageous

- Jo Brassington and Adam Brett – Pride and Progress

- Shaun Dellenty – Celebrating Difference

- Catherine Lee – Pretended

- Daniel Tomlinson-Gray – Big Gay Adventures

Podcasts:

Blogs:

- Amy Ashenden – Faith as a Barrier

- David Church – Take Back the Narrative

- David Lowbridge-Ellis – Keep Chipping Away

- David Weston – Pride Matters

- Dominic Arnall – Primary School Storytime

- Dominic Arnall – Section 28 is Still Hanging Over Us

- Gerlinde Achenback – Age Appropriate

- Ian Timbrell – Fight Against RSE

- Jared Cawley – My Wellbeing

- Katherine Fowler – Audit Your Curriculum

- Peter Fullagar – Don’t Look Back

- Rob Ward – Parents Support It and Students Want It

- STEP Study – Improving Support

- Vicki Merrick – Increasingly Visible

Resources:

- Bethan Hughes and Holly Parker-Guest – LGBT+ Inclusion toolkit

- David Lowbridge-Ellis – The Queer Knowledge Organiser

Training:

'Teaching Transgender Awareness Using No Outsiders' - new film resource for schools

Written by Andrew Moffat

Andrew Moffat has been teaching for 25 years and is currently PD Lead at Excelsior MAT. He is the author of “No Outsiders in our school: Teaching the Equality Act in Primary Schools” and “No Outsiders: everyone different, everyone welcome”. In 2017 Andrew was awarded a MBE for services to equality and diversity in education and in 2019 he was listed as a top ten finalist in the Varkey Foundation Global Teacher Prize.

This week is Transgender Awareness Week which is a great opportunity to launch our new film, “Teaching Transgender Awareness using No Outsiders. The film shows that there are trans children in our schools today and many of those schools are doing an excellent job keeping them safe.

The Keeping Children Safe In Education guidance (Gov.UK, 2023) sets out expectations for schools to safeguard LGBT children;

“Risks can be compounded where children who are LGBT lack a trusted adult with whom they can be open. It is therefore vital that staff endeavour to reduce the additional barriers faced and provide a safe space for them to speak out or share their concerns with members of staff.” (para 204)

Schools in England and Wales are currently waiting for DfE guidance on gender and gender identity. In July 2023, The Times reported that proposed gender guidance had been pulled;

“A Whitehall source said that No10 and Badenoch had out forward a series of proposals to strengthen the guidance to the attorney general and government lawyers. The strongest – and a reflection of the governments concerns – was a blanket ban on social transitioning.” (Swinford, 2023)

The article quoted a government source saying:

“More information is needed about the long term implications of allowing a child to live as though they are the opposite gender and the impact that may have on other children too.” (Swinford, 2023)

The aim of this new film from No Outsiders is to show that schools are already working successfully with trans children and their parents. Schools are delivering age-appropriate lessons where children demonstrate knowledge and understanding and are taught about non-judgement, respect and acceptance of others.

My aim was to make a gentle film to take the heat out of the debate. In the film, we see Sam, a trans man living in Birmingham, return to his primary school to meet his former Y6 teacher. Sam sits in the seat where he sat as an 11 year old, and they discuss how his life has changed since then. His teacher describes how the school has moved on to reflect equality and inclusion today. Sam watches and comments on footage of a No Outsiders lesson at a school in Hertfordshire where transgender awareness is taught, and we hear Year 6 children speak eloquently on the subject. The film shows two parents (one is Sam’s Dad) talking about their experiences bringing up a trans child and the huge support they received from their respective schools. We also see Year 6 children in Bristol discuss texts used in their lessons and respond to the question, “Are you too young to know about this?”

I really wanted to show in this film that parents are working with schools, schools are listening, teachers are working hard to get it right. There is nothing scary or unusual about this. As teachers, we are good at putting the best interests of the children we teach at the heart of our policy and practice. My message to the DfE is, please let us get on with it. Schools want to get this right; we want to work with parents and children to create an environment where every child knows they belong.”

So, what now? What to do with the film? My first thought was to put a link on X (formerly twitter) and the No Outsiders facebook page, but I am aware of the toxic debate around this subject currently and I want to protect all the children and adults in the film. Of course, I realise once it is up on youtube, I lose control of who watches and where it goes, and in the coming months it may well pick up negative responses. but I feel in the first few weeks at least, for the first few views I would like allies to be seeing it. So, I immediately thought of Diverse Educators; a place where educators meet and support each other to make the world a better place. This should be the early audience for the film. Please feel free to share with friends and colleagues, show in staff meetings and use as a stimulus for discussion. I want people to see it. I hope people find it useful.

Watch the film here and feel free to share as you wish. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIH7I_SEU0E&t=3s

What is No Outsiders?

The ‘No Outsiders’ programme was created in order to build an ethos of community cohesion and respect for difference. It has had a positive impact on schools, teachers, children, and communities and has received widespread commendation within the education sector. In 2017, CEO Andrew Moffat was awarded an MBE medal by The Queen (UK) for equality and diversity work in education. In 2019 he was a top 10 finalist in the Varkey Foundation Global Teacher Prize: a $1million award for outstanding contributions to the profession.

Teacher training related to the ‘No Outsiders’ programme has had widespread recognition. In the year 2023 January – November, Andrew Moffat has delivered No Outsiders training in 85 schools across the UK, and at numerous conferences and events, teaching over 35,000 children a No Outsiders lesson and training over 11,000 staff.

The No Outsiders guide “No Outsiders: everyone different, everyone welcome” is available here https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?k=andrew+moffat&crid=3OT7CA7JHVOS2&sprefix=%2Caps%2C308&ref=nb_sb_ss_recent_1_0_recent

A new No Outsiders scheme will be published April 2024.

Has EDI become a commercial business?

Written by Zahara Chowdhury

Zahara is founder and editor of the blog and podcast, School Should Be, a platform that explores a range of topics helping students, teachers and parents on how to ‘adult well’, together. She is a DEI lead across 2 secondary schools and advises schools on how to create positive and progressive cultures for staff and students. Zahara is a previous Head of English, Associate Senior Leader and Education and Wellbeing Consultant.

Last year, on my return to work after a short maternity break, I wrote a very candid post about leading EDI in schools. Almost a year on, I have had some wonderful opportunities with DiverseEd, The GEC, Teachit, Edurio, Schools Week, SecEd, Middle East Eye…all talking about diversity, equality and inclusion in education. Now working in the Higher Education sector, I am learning so much about intent vs impact, using Driscoll’s model of reflection. In using Driscoll’s model, I find myself questioning the EDI ‘work’ more and more – not its necessity (believe me, it’s more needed than ever), but whether or not it is making a sustainable impact and lasting change, or whether it is simply at risk of being a step on a ladder, a set of buzz words and a marketing asset for schools and organisations.

Is it right to be an EDI Lead?

George Floyd’s murder can be regarded as a watershed moment for anti-racism work, but also for diversity and inclusion. With the rise of Gen Z, Gen Alpha and social media, the EDI landscape has, in many ways, rocketed and quite rightly so. Although many think it drives a cancel culture and a call out culture, it has also led to meaningful change for people with protected characteristics. Equally, a growing number of companies are making EDI roles bigger, smaller or redundant. Speaking to friends and colleagues in the ‘field’ (especially global majority heritage colleagues), it seems EDI is a thriving, purposeful business, but one which is exhausting and draining too. To be completely candid, I have reflected and wondered whether I am toxically ‘profiting’ from my own ‘EDI’ trauma, story, knowledge, expertise (whatever you want to call it) and sometimes feel a level of guilt, imposter and also, loss.

It’s tough being vulnerable in the public and professional eye, laying bare your identity for the sake of strategy, culture, governance, policy and practice. I also worry about what’s next? Not necessarily because I think EDI will become redundant (this thought in itself is problematic and misplaced). Rather it is mentally and physically tough to work in a field so rich and granular, that I worry where and how the energy can be sustained.

The work is purposeful, important and of value. However, for it to be impactful and fulfilling we must start holding organisational leads, middle management, policies and practices to account. If there are policies and practices which have a detrimental, and historic impact on individuals with protected and non-protected characteristics (socio-economic status for example), no amount of training is going to fix that. Experience and very loose, qualitative research (candid conversations!) reveals consistency and commitment to inclusion at middle management level is just as important (if not more) to creating a culture of belonging.

To flip from business to culture, it is integral that leaders and managers intentionally and uncomfortably make the difficult changes necessary to create equitable work environments. Celebrate whistleblowing and call our culture, scrutinise and fix representation gaps, embrace flexibility and use positive action, inclusive recruitment strategies; do what you have to do to create a trusting and lasting culture for every employee and student.

Diversity across the curriculum is scratching the surface.

Whilst a diverse curriculum and EDI training is wholly important, and can have a life changing impact on young people (especially Early Years), it is but one cog in a set of very large and complex wheels. In my relatively short time of working in this space, I’ve learned just how easy it is to become a ‘tickbox’ or a ‘box ticker’, without even realising. All too often EDI is boxed in; it’s carved out like an isolated gym session (stick with me). We all know 1 run, 1 personal training session, or 1 class a week will not make a difference to our health unless we see to our eating habits, our mindset, consistency, our NEAT actions. A brilliant guest speaker may leave us high on endorphins like a Spin class, but then what? EDI is a hard, constant and ‘infinite’ journey that should never be redundant or complete – the world is ever-changing and diversifying, in our lifetime at least. If this thought leaves you exasperated or frustrated, flip those feelings and be curious instead: it provides a perfect opportunity to speak to an EDI specialist or students and staff with protected characteristics to ask, how can inclusion and belonging become an active part of day-to-day, micro and macro policies and practices in your workplace? Listening is important, developing and actioning a plan is fundamental.

In her book, The Courage of Compassion (2023), Public Defender, Robin Steinberg says ‘the struggle for social justice is won […] one person at a time’. With every feeling of imposter and exhaustion I simultaneously realise just how purposeful, impactful and necessary equality and diversity is – in education, the workplace and society. Of course, the ‘business’ of finding solutions and making a tangible impact is very important, however the ongoing work, the self-reflection, the side-by-side influences, are perhaps integral to keeping diversity and inclusion at the centre of every business and organisation.

Launching a network for new leaders made me a better ally

Written by Ben Hobbis

Teacher, Middle Leader and DSL. Founder of EdConnect and StepUpEd Networks.

Are you a new leader, like the idea of leadership but struggle to find the balance between teaching and leading? Are you someone who wants to lead or be a leader, but not knowing how to get there, feeling a bit stagnant? You might be a leader developing, but in the wrong organisation? You might not see leaders like you? This is why Step Up was set up.

Step Up is a new network for new and aspiring leaders in education, particularly at middle and senior leadership levels in schools. Upon starting the social media account, and subsequent network, we surveyed people to find out who our community are and what they want/need. This has been incredibly useful. It’s been great getting to know our community.

From this research and insight, we have constructed five ‘leadership themes’ that we base our content and output around. We base our speakers, events, blogs and much more around these themes. The five themes are: Leadership Journeys, Leadership Barriers & Challenges, Leadership Development, Leadership Wellbeing and Leadership Diversity. Now, whilst many of these will overlap when people speak, present and write to these.

I personally as the founder wanted to ensure that whatever we do, we are inclusive and that we are diverse in order to create a community where our network members belong. Now, as a heterosexual, white, able bodied, cisgender man who doesn’t have children and is fairly financially stable, I know I’ve had it easier than others. However, I have always committed to be an inclusive ally and a HeForShe ally also. I have been a keen supporter and champion of Diverse Educators since signing up to social media and their journey started. One thing I have released is that I’ve continued to learn as an ally.

One of the biggest learning curves was Step Up’s Launch Event. As I co-hosted alongside one of my fellow network leaders, WomenEd’s own Elaine Hayes, I listened attentively to our speakers. I listened to their vulnerability; to their negative and positive experiences; to their struggles; to their hopes and wishes; to their experience and tips. I felt quite emotional in parts listening to in some cases abhorrent behaviour that they (or colleagues, friends or family) had been subjected to as part of their journey.

I’ve summarised some of the key takeaways from some of the presentations, that may be useful for the audience reading this…

Parm Plummer, WomenEd’s Global Strategic Leader and a Secondary Assistant Headteacher based in Jersey presented on Women in Leadership. Her talk initially started with sharing the fantastic work of WomenEd: their campaigns, partnerships, networks (including their global reach) and the development opportunities they provide for female leaders. Parm then went on to help navigate the process of stepping up as a female leader. Initially, sharing the only image of a woman that came up during a Google search; before going on to provide tips to write a job application through to negotiating your terms. Parm gave tips including finding allies and joining networks.

Helen Witty, a neurodivergent Lead SENDCo based in the East of England who gave a pre-recorded video on Neurodivergent Leadership. She shared an insight into her job and life, as a SENDCo with ADHD. She shared about how being open about her ADHD at her job interview and how it positively impacts her life and those who she works with. Helen also gave a fantastic insight into the role of a SENDCo, for all those who aspire to this role.

Stephanie Shaldas, a secondary deputy headteacher leading on diversity and inclusion based in London. Her talk Leadership in Colour: Senior Leadership as a Black American Woman started with a story from March 2021 whilst she was working as an Acting Co-Headteacher. This story was based around Prince William visiting her school. What was a forty-five minute visit, led to a weekend of trending on Twitter, including one Tweet: ‘Who dressed up the secretary in African cloth and trotted her out?’ Stephanie went onto talk about her journey and how she felt like school leaders didn’t look like her, when she was in her early career. She shared her inspiring path to leadership including her own education as well as teaching and leadership roles at middle and senior level spanning both curriculum and pastoral. As Stephanie said, “If I can, then you can!” – find your why and explore your passions!

Mubina Ahmed, Head of Science Faculty, based in London gave a presentation titled: ‘Using my minority lens to lead.’ Mubina went on to talk about how she used her minority ethnic background to her strength in her leadership journey. She posed the key question: ‘Do we have equity in teaching?’ Mubina used research and evidence to back up every piece of advice and information that she gave; talking about building allies to help you bring your chair to the table.

Albert Adeyemi, co-founder of Black Men Teach and a Head of Year based in the East of England gave a talk based around wellbeing and belonging in leadership. He spoke eloquently about the importance of wellbeing, how every interaction with others builds up to this. He narrated the sense of being needed versus feeling wanting and knowing what you need to fill your cup, to achieve wellbeing and belonging. The part that really blew me away was a surprise from Albert, a spoken word about belonging; a part of the event which brought a tear to my eye.

Jaycee Ward, a phase leader in a Yorkshire primary school, spoke about imposter syndrome, based around her journey as a young senior leader. Jaycee narrated her journey to date and how she has completely changed her narrative and inner critic. She shared her five top tips for combatting imposter syndrome: Seek Support, Embrace Vulnerability, Celebrate Achievements, Self-Compassion, Self-Reflection. Something, everyone at the event resonated with.

Nicola Mooney, a secondary deputy headteacher based in the South West of England, who also volunteers for WomenEd and MTPT Project, gave an interesting presentation on ‘non-linear career paths’. She shared her journey through her career to date including multiple maternity leaves and periods of IVF. Nicola shared how by not going through the ‘traditional’ upward trajectory has enabled her to be successful both as a teacher and as a mother. It was a talk many welcomed, knowing it is not as simple and always useful to be continually promoted.

I feel very privileged to have spent time in the virtual room with these fantastic Diverse leaders. Step Up (and I) will continue championing for diversity, equity, and inclusion within the education leadership sector; and will ensure everyone has the chance to share their stories. If you want to get involved and find out more, then follow us on X (formerly Twitter) @StepUpNet_Ed and check out our website: www.stepupednet.wordpress.com.